The writer Aventinus stated that the Minne and the Minnesingers did not have anything to do with love and constant courting. That’s not entirely true. There are many enigmas and paradoxes concerning the Troubadour movement and their theme “LOVE” in the middle ages. They propagated the quest for selfhood, the birth of the individual. And the individual’s love is discriminative, personal and specific.

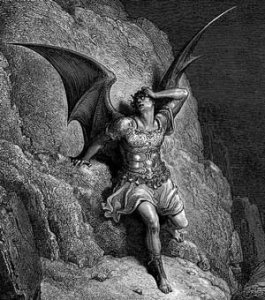

You will have heard the old legend of how, when God created the angels, he commanded them to pay worship to no one but himself; but then, creating man, he commanded them to bow in reverence to this most noble of his works, and Lucifer refused—because, we are told, of his pride.

However, according to this Moslem reading of his case, it was rather because he loved and adored God so deeply and intensely that he could not bring himself to bow before anything else. And it was for that that he was flung into Hell, condemned to exist there forever, apart from his love.

However, according to this Moslem reading of his case, it was rather because he loved and adored God so deeply and intensely that he could not bring himself to bow before anything else. And it was for that that he was flung into Hell, condemned to exist there forever, apart from his love.

The Persian poets have asked, “By what power is Satan sustained?” And the answer that they have found is this: “By his memory of the sound of God’s voice when he said, ‘Be gone!’ What an image of that exquisite spiritual agony which is at once the rapture and the anguish of love!

Another tale from Persia is in the life and words of the mystic al-Hallaj, who in A.D. 922 was tortured and crucified for having declared that he and his Beloved—namely God—were one. He had compared his love for God with that of the moth for the flame. The moth plays about the lighted lamp till dawn, and, returning with battered wings to its friends, tells of the beautiful thing it found; then, desiring to be joined to it entirely, flying into the flame the next night, becomes one with it.

The great German philosopher Schopenhauer, in a magnificent essay on “The Foundation of Morality,” treats of transcendental spiritual experience. How is it, he asks, that an individual can so forget himself and his own safety that he will put himself and his life in jeopardy to save another from death or pain—as though that other’s life were his own, that other’s danger his own?

Such a one is then acting, Schopenhauer answers, out of an instinctive recognition of the truth that he and that other in fact are one.

He has been moved not from the lesser, secondary knowledge of himself as separate from others, but from an immediate experience of the greater, truer truth, that we are all one in the ground of our being. Schopenhauer’s name for this motivation is “compassion,” Mitleid, and he identifies it as the one and only inspiration of inherently moral action. It is founded, in his view, in a metaphysically valid insight. For a moment one is selfless, boundless, without ego.

It’s all again paradoxical. Take the legend of the love potion of Tristan and Isolde, where it is indeed the paradox of the love mystery that is celebrated: the agony of love’s joy, and the lover’s joy in that agony, which is by noble hearts experienced as the very ambrosia of life.

“I have undertaken a labor,” wrote the greatest of the great Tristan poets, Gottfried von Strassburg, from whose version of the legend Wagner took the inspiration for his opera, “a labor out of love for the world and to comfort noble hearts: those that I hold dear, and the world to which my heart goes out.” But then he adds: “Not the common world do I mean, of those who (as I have heard) cannot bear grief and desire but to bathe in bliss. (May God then let them dwell in bliss!)

Their world and manner of life my tale does not regard: its life and mine lie apart. Another world do I hold in mind, which bears together in one heart its bitter sweetness and its dear grief, its heart’s delight and its pain of longing, dear life and sorrowful death, dear death and sorrowful life. In this world let me have my world, to be damned with it, or to be saved.”

Marriage in the Middle Ages was almost exclusively a social, family concern—as it has been forever, of course. Particularly in aristocratic circles, young women hardly out of girlhood were married off as political pawns. And the Church, meanwhile, was sacramentalizing such unions with its inappropriately mystical language about the two that were now to be of one flesh, united through love and by God: and let no man put asunder what God hath joined. Any actual experience of love could enter into such a system only as a harbinger of disaster.

For not only could one be burned at the stake in punishment for adultery, but, according to current belief, one would also burn forever in Hell. And yet love came, even so, to such noble hearts as were celebrated by Gottfried; not only came, but was invited in. And it was the work of the troubadours to celebrate this passion, which in their view was of a divine grace altogether higher in dignity than the sacraments of the Church, higher than the sacrament of marriage, and, if excluded from Heaven, then sanctified in Hell. And that the word amor was the reverse in spelling of Roma seemed marvelously to epitomize the sense of the contrast.

For not only could one be burned at the stake in punishment for adultery, but, according to current belief, one would also burn forever in Hell. And yet love came, even so, to such noble hearts as were celebrated by Gottfried; not only came, but was invited in. And it was the work of the troubadours to celebrate this passion, which in their view was of a divine grace altogether higher in dignity than the sacraments of the Church, higher than the sacrament of marriage, and, if excluded from Heaven, then sanctified in Hell. And that the word amor was the reverse in spelling of Roma seemed marvelously to epitomize the sense of the contrast.

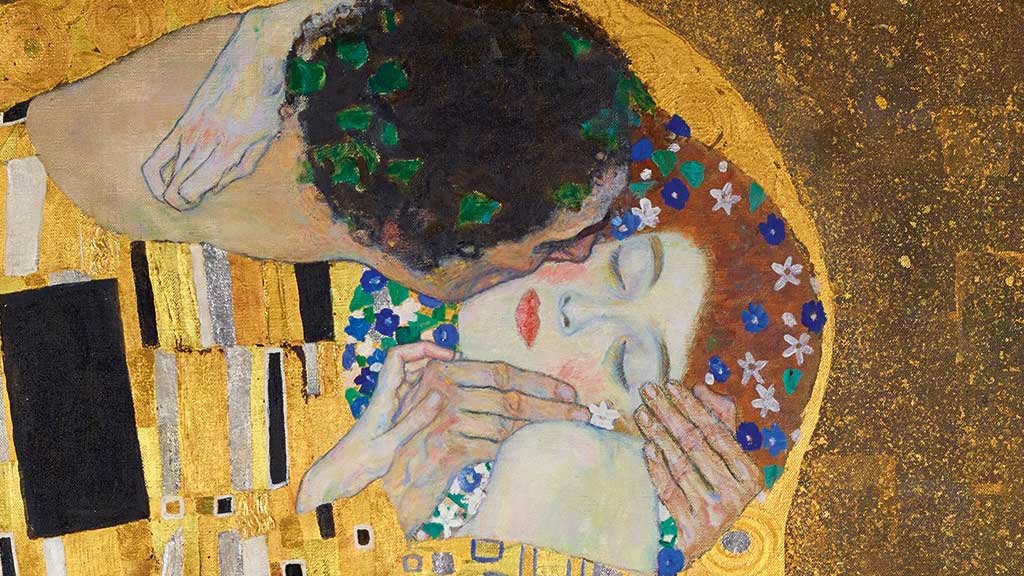

Debates of the troubadours on the subject were a favorite theme of their poems, and the most fitting definition achieved as that which has been preserved to us in a stanza by one of the most respected of their number, Guiraut de Borneyl, to the point that amor is discriminative—personal and specific—born of the eyes and the heart.

So, through the eyes love attains the heart:

For the eyes are the scouts of the heart,

And the eyes go reconnoitering

For what it would please the heart to possess.

And when they are in full accord

And firm, all three, in one resolve,

At that time, perfect love is born

From what the eyes have made welcome to the heart.

Not otherwise can love be born or have commencement.

Than by this birth and commencement moved by inclination.

Such a noble love discriminates. It is not a “love thy neighbor as thyself no matter who he may be”; not charity or compassion. Nor is it an expression of the general will to sex, which is equally indiscriminate.

It is of the order, that is to say, neither of Heaven nor of Hell, but of earth; grounded in the psyche of a particular individual and, specifically, the predilection of his eyes: their perception of another specific individual and communication of her image to his heart—which is to be (as we are told in other documents of the time) a “noble” or “gentle” heart, capable of the emotion of love, amor, not simply lust.

More to come

A good read:

https://amzn.to/2V1twKl