The British enjoy deceiving their enemies. When the Prussian strategist Carl von Clausewitz defined war in 1833 as ‘those acts of force to compel our enemy to do our will’, he missed out the dimension that the British political philosopher Thomas Hobbes had spotted nearly two centuries earlier: ‘Force and fraud are in war the two cardinal virtues.’

‘The British like to pretend,’ observes a former US Ambassador, Raymond Seitz. ‘They seem to prize few things so much as a good performance.’ And the theatre director Richard Eyre notes the national ‘love of ritual, procession . . . and dressing-up’. ‘On the surface they are so open,’ writes novelist Geoffrey Household of his countrymen, ‘and yet so naturally and unconsciously secretive about anything which is of real importance to them.’ British self-deprecation, wit and irony are also forms of concealment. The British do not say what they mean, or mean what they say, and often mask seriousness with jokes as a cover for shyness or sentiment. Jorge Luis Borges says of Herbert Ashe in Ficciones: ‘He suffered from unreality, like so many of the British.’

Of course, military deception (MILDEC), which the US Joint Chiefs define as ‘actions executed to deliberately mislead adversary decision makers as to friendly military capabilities, intentions and operations’, has been used all over the world. In China 2,400 years ago, Sun Tzu said in The Art of War that ‘All warfare is based on deception’. The hadith or proverb, ‘al-harb khuda’, attributed to the Prophet Muhammad – peace be upon him – also means ‘war is deception’.

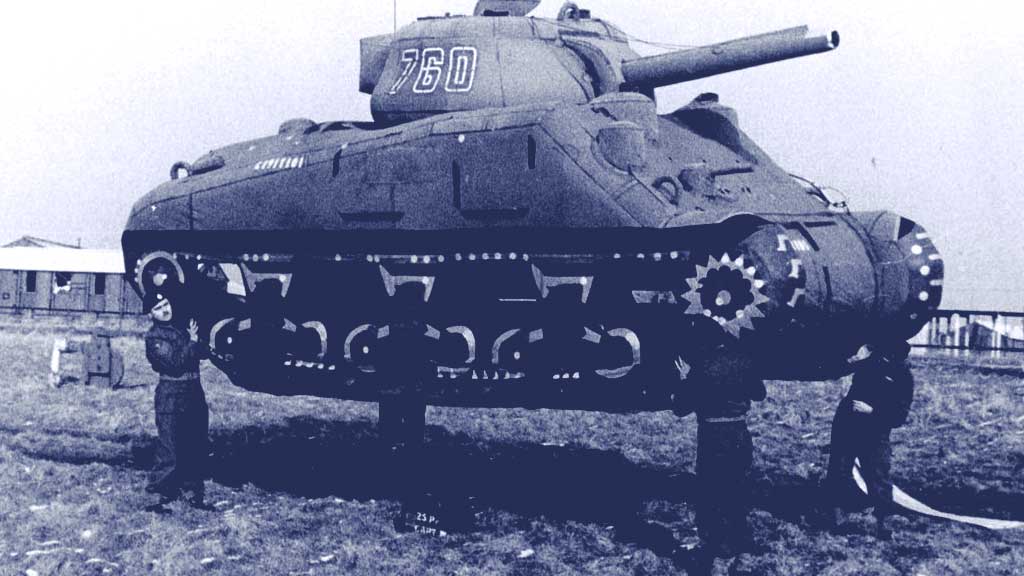

The British developed deception in both World Wars as a response to dangers represented by new military technologies on land, at sea and in the air. This was especially true in WW2, when the weakened nation had its back to the wall after the rest of Europe had fallen into what Churchill called ‘the grip of the Gestapo’.

Military deception

This book argues that British twentieth-century military deception has four pillars: camouflage, propaganda, secret intelligence and special forces. Churchill was excited by T. E. Lawrence’s ideas about guerrilla warfare, based on disguise and surprise rather than frontal assault, and it was in Churchill’s prime ministership that the Commandos and the SAS were founded. He also became a master of propaganda who, as the broadcaster Edward R. Murrow said, ‘mobilized the English language and sent it into battle’.

Native cunning links all Churchill’s wizards, creative people using their skills to help their country in a struggle for survival. The two World Wars recruited widely from the nation’s pool of talent, not just from the narrow caste of professional soldiers. This book “A genius for deception” is about artists and scientists, film and theatre people, novelists and journalists. The second half of the book is about WW2, and introduces German-speaking Daily Express journalist Sefton Delmer (see also another post on the occult adepts in MI6 and MI5) and a hyper-observant, cinema-loving regular soldier called Dudley Clarke.

These 2 twin avatars of British strategic deception and black propaganda in WW2, were both men pulled between two worlds. Dudley Clarke was an artistic type, inventive and theatrical, who had to find an outlet for his creative ingenuity within the rigidities of the British army. Sefton Delmer was brought up in Germany. During the First World War he was the sole British pupil in his Berlin school; when his family moved to Britain, he became the only German-accented boy in a wartime English public school. Delmer, Clarke and their cohorts wove an ever more complex web of tactical trickery, strategic deception and black propaganda to help the Allies win the war.

Delmer’s exploits in this book are written as a true adventure novel.

A interesting read and “entertaining journey.”