https://amzn.to/2URJebK

At 3 o’clock Sunday morning, November 4, 1956, I returned to the hotel in Vienna where I had been staying for three days.

I paused to leave a call and exchange a few idle words with the hall porter. Nostalgic early morning music from the radio behind the telephone switchboard echoed through the empty lobby.

I went to my room, and within a few minutes after getting into bed, was asleep. At five minutes past 4 the telephone rang. Switching on the light, I reached sleepily for the receiver, my brain stumbling through possible reasons for a call at such an hour. It deliberately side-stepped the possibility that was all too real. Knowing but discreet, the hall porter’s voice came through to me.

Hungary 1956

“Sir,” he said, “there is an emergency broadcast coming from Hungary. Imre Nagy, the Prime Minister, is speaking. I thought you would be interested. Just a moment, I’ll put the telephone next to the radio. “And so I lay in the Vienna night and listened to the voices of Nagy and interpreters announcing, in terse and stricken but courageous tones, that the Russians had attacked Budapest at 2 o’clock that morning. They were recordings, made less than an hour before, and were repeated continuously in Hungarian, Russian, French, English, and German. I turned cold. I continued to listen, stunned, hoping for a word that it was not true.

Russian tanks

Over and over, the Magyar accents repeated the brief and terrible announcement in the five languages. I lay there, picturing the columns of Russian tanks advancing through the darkened streets, firing mercilessly into the crowded apartments, into the proud and poignant city only four hours’ drive to the east—a city I had known well. The porter’s voice brought me to my senses. I thanked him, put down the receiver, and considered what I had to do. The answer was nothing. As the Russians well knew, if anyone had fomented the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, that astounding moment of truth shared by a whole people, it was the Russians themselves and their handful of Hungarian servants.

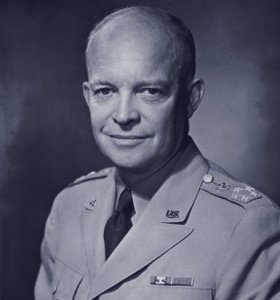

We, the Americans, had nothing to do with it. In the two weeks since its eruption, the United States had substituted baffled wonderment for a policy, and was headless besides. The President was campaigning for re-election. The Secretary of State, who carried foreign policy in his hat, had had to temporarily hang it up while undergoing surgery. The Department of State was being run by a first-rate petroleum engineer.

Observer

The Russians, it must be said, were equally baffled. They hesitated and vacillated. The night’s news meant that they had finally estimated the American reaction—correctly, as it turned out—and had therefore found a policy—now being put into effect with the guns of the Red Army. My own purposes at Vienna were simple enough. The political operations in which I was engaged concerned Hungarians outside of Hungary, and my principal tasks had to do with the tens of thousands of Hungarian refugees pouring over the border into Austria.

So far as events in Hungary were concerned, my mission was purely that of an observer. If a contact should develop with the new Hungarian revolutionary regime, I would maintain it while seeking new instructions. Indeed, only eight days before, an exiled Hungarian, a former very high postwar politician and Cabinet Minister, had told me that he had telephoned Budapest and spoken to members of the new Imre Nagy Cabinet, who had said simply, ” Speak for us in the West Make them understand our neutrality.”

I had assisted this man then to travel to Vienna, not with the intention of his re-entering Hungary, but only so that he could be in closer contact with his colleagues and compatriots now in the Government. He had, on arrival in Vienna, been immediately deported to Switzerland on, of all things the representations of the American Ambassador to Austria.

I had, therefore, on my own arrival in Vienna, sent word to one of his henchmen who was now somewhere in Hungary carrying a letter from the former Minister to the leading non-Marxist political personality in the new Government. There was nothing I could or need do about this courier. I telephoned to a post near the Austro-Hungarian border. Here I learned only that the border was still open, refugees were still crossing. While the sounds of heavy gunfire could be heard on the other side, from the direction of Gyor, the nearest large town.

British and French cynicism

That done, I think I briefly lost my reason. A boiling rage overcame me. It was as though a fever swept through my brain. I did not curse the Russians —I seemed to feel almost that I knew them too well for that. I did not rant at our own impotence. The American Government seemed to me somehow pitiful and irrelevant at that moment, hardly to blame for its troubles. My anger instead was vented upon the British and French.

I wildly blamed their adventure at Suez for giving the Russians the pretext for their action in Hungary. And I swore, in a kind of momentary delirium, that I would never again set foot in France or England. I would devote myself to exposing their monstrous cynicism in sacrificing Hungary for Suez, and so on. (Secret agents are not necessarily coldly unemotional and the secret agent’s objectives are to him, necessarily, of paramount, and highly personal, importance.)

None of this had anything to do with the facts, of course. The British and French operation at Suez was conceived and prepared well before the Hungarian Revolution of October. Which took the British and French, as I well knew, as much by surprise as it did the Russians and Americans. I realized all this in the morning, after a few hours’ sleep—and I also remembered the past, which did much to explain the seizure which had overcome me in the night. But the preface to that story of the past is—a short course in the secret war…

The secret war

At the end of the Second World War the American public generally felt that the fighting was over. Postwar problems were recognized to exist, but they seemed, to most Americans, to involve such things as rehabilitation, economic questions, some political negotiations—but nothing of conflict Organized mothers groups in 1946 cornered the Chief of Staff of the United States Army—later to become President—in the halls of the Capitol, preventing him from attending Congressional hearings while they demanded he “bring our boys back home.” In the same period, the largest mass-circulation magazine in the country exulted in an editorial entitled “The American Century.”

The mood was one of a problem definitely solved, and of power. But the secret war had already begun. The power was real, even if the mood was contradictory and in some respects reckless. But power in human affairs has its own organic characteristics. It both attracts and repels. In either case it inspires an underlying, even subconscious fear.

https://amzn.to/2URJebK

A Short Course in THE SECRET WAR

A Short Course in THE SECRET WAR is neither a scholarly treatise nor a historical survey nor a textbook. It is simply a record of my own recollections, experiences, impressions, reflections, and conclusions resulting from some sixteen years in secret operations, all in the service of the United States, and in a variety of countries and organizations. It is my hope that from this informal collection there will gradually emerge for the reader that understanding of the principles of secret operations which is the purpose of the book. Beyond that, it is my hope that, from the personal opinions, criticisms, and comments which occur throughout, and for which I take sole responsibility, the reader will gain some idea of the hard realities and problems which face those responsible for these activities…

—Christopher Felix

A Short Course in THE SECRET WAR