In Celtic Scotland there exist plenty traditions of sacred locations, places and folklore about people crossing into the Otherworld, a number of which are identified with sorcha (pronounced “sahkhaa”). This is an ancient phrase that means both ‘paradise’ and ‘illuminated being.’ Once again there’s a similarity with Egypt. Because the syllable ka is their word for ‘risen soul or awareness.’

Sidh Chailleann is the core of Scottish Otherworld tradition. This mountain marks the geodetic center of the country. The name means ‘hill of the Sidhe’ or ‘hill of the Faery Realm.’ On the west shoulder of Schiehallion (as it’s known today), approximately two-thirds of the way up to its pyramidal summit lies a cave the Celts peopled with fairies and goblins, its folklore committed to paper by a local nineteenth-century parish priest:

There is a very remarkable cave near the south-west angle of Sithchaillinn, at the Shealing, called Tom-a-mhorair (cave of the giant). Some miles to the east, there is an opening in the face of a rock, which is believed to be the termination thereof.

Several stories are told and believed by the credulous, relating to this cave; that the inside thereof is full of chambers or separate apartments, and that, as soon as a person advances a few yards, he comes to a door, which, the moment he enters, closes, as it opened, of its own accord, and prevents his returning.

From MacDonald, The New Statistical Account for Scotland, vol. X.

According to Reverend MacDonald, the stories were related by people who “may be characterized as intellectual, sober, and industrious in their habits, honest and religious.”

The Culdee

The only people known to have frequented this abode of supernatural beings were individuals believed to have been initiated into the secrets of nature, a tradition traced back to an autonomous group of local hermit monks named the Culdee, who once were associated with the early Celtic Church.

Formerly known as Chaldeans (from the Aramaic Khalid, ‘Friend of God’), they migrated from Asia Minor, and their practices were extensions of Druid, Manichean, and Essene beliefs, all of which shared the same tradition of initiation and living resurrection.

The island of Mull

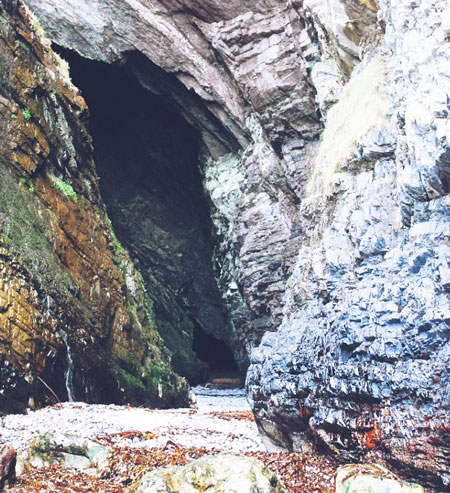

This tradition finds its counterpart on the island of Mull, stepping stone to the sacred isle of Iona. Mull’s own venerable holy mountain, Ben Mhor, rises formidably above an unusual feature: an enormous cave with a mouth gaping at the Atlantic and wide enough to swallow the setting sun.

MacKinnon’s Cave is connected with many eerie legends. Folk tales describe initiates performing rituals there during pagan times on a massive flat stone called Fingal’s Table, which rests in a chamber deep inside this horizontal volcanic tube.

Certainly the environs are protected by enough superstition to keep the superficially curious away, in addition to a sea that enters the cave and flows far inland with the rising tide.

It is said that the cave’s recesses pass right through the mountain to the other side of the island, allowing those so inclined to enter in the west and emerge into the sunrise in the east.

That was then. Today the rear of the cave is blocked by sand and debris, but assuming the legend is true and the natural chasm does run beneath the island—such volcanic features are common in this part of Scotland—an easterly line projected across Mull does arrive at the mouth of Uamh na Nighinn (Cave of the Young Maiden), an unusual name given its isolation from any settlement and accessible only from the sea.

Could its given name imply a communion with the divine virgin to whom initiates were wedded? Perhaps. And as if this wasn’t coincidence enough, the distance between the two cave mouths is 18.6 miles, the same number in years as the lunar cycle.

Resurrection Mystery

That the resurrection Mystery was performed in some fashion in this area may be commemorated in the unusual behavior of Odhràn, a sixth-century Celtic Christian monk who, upon reaching the adjacent island of Iona with St. Columba, rebuilt a ruined chapel previously built by the Culdee. Legend states that the walls of the chapel came down as fast as they went up as though by evil intent; only when a person was buried alive inside would the stones remain upright.

Odhràn volunteered for the task, and when the earth was removed three days later, Odhràn raised himself and declared that all that had been said of hell was a joke. Clearly this monk experienced something inside this ancient place of veneration that changed his outlook on the true nature of reality.

The Culdee’s alleged arrival in the British Isles circa AD 376 is supported by the fact that this small chapel aligns to the simultaneous rising of Venus and the sun on the spring equinox of that year. Again a link with Venus.

Incidentally, the Druids (Gaelic, ‘magicians, wise men’) were known to have conjured the weather against St. Columba when he tried to boot them and the Culdee out of Iona. Or perhaps the gesture was aimed at Columba’s distaste of women, for Iona and Mull point to a tradition of ritual whereby women were very much involved, seeing as a disproportionate number of churches and monasteries were maintained by female orders, including Eilean nam Bam, the Island of Women, while the Druid and Culdee monks themselves were known to have been married…

Otherworld and Tintagel

The examples throughout the British Isles of anomalous ceremonial mounds and chambers are too numerous to list, but one in particular merits attention due to its long association with the Celtic Otherworld—an island of volcanic rock and slate barely tethered to the mainland of Cornwall—Tintagel.

It is the quintessential ‘island in the west’ to where the soul migrates in resurrection traditions. Indeed, by its geographic location, at Tintagel one physically prepares to embark on a westward journey into the endless Atlantic horizon. The entire mass even sits on a magnetic anomaly, giving the site a palpable aura of a place set aside from the physical world.

Unlocking the secret

The clue to unlocking Tintagel’s secret lies across the way, on the edge of a precipitous mainland cliff, where stands a rare fifth-century church dedicated to Madryn, a Welsh princess said to have birthed a divinely conceived child. The name is most likely a corruption of Mater Ann, the mother of the gods.

Beside the church were found slate graves devoid of bodies, but bearing a cache of goods from southeast Turkey. How odd that tomb robbers should have pinched the corpses but left the precious gifts behind. These graves encircle an ancient mound beneath which was found a large polygonal chamber aligned east-west, featuring a hollowed greenstone used for ritual libations. It too was devoid of burial.

At the center of these anomalous features stands an unusual conical stone cut from mica. It marks the edge of one of Europe’s most studied pathways of naturally occurring energy, the Morganna line.

However, it also doubles as a sighting post used for aligning the Great Bear and the pole star that rise over Tintagel island just before the sun is reborn on the winter solstice.

This is very significant because, according to indigenous traditions, souls incarnate from the still point of the sky—the pole star—travel along an invisible tube to Earth, and return through it at death. There’s always more than meets the eye.