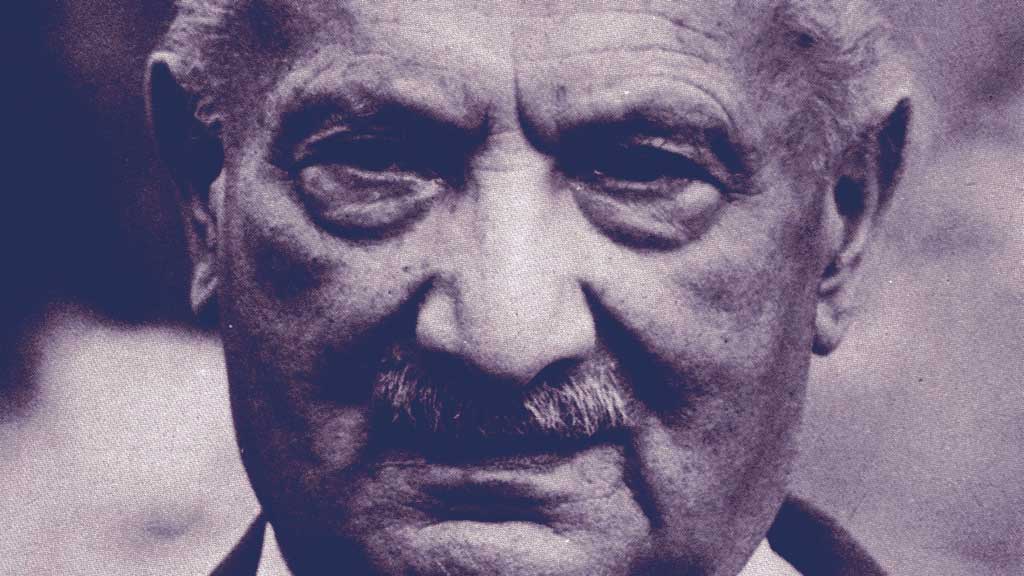

Heidegger’s Being and Time (1924), a quickly written introductory volume to a proposed multi-volume project, inspired philosophers for generations to come. What did the enigmatic title refer to? “As regards the title ‘Being and Time,’ ‘time’ means neither the calculated time of the ‘clock,’ nor ‘lived time’ in the sense of Bergson and others,” he explained, years after the book appeared.

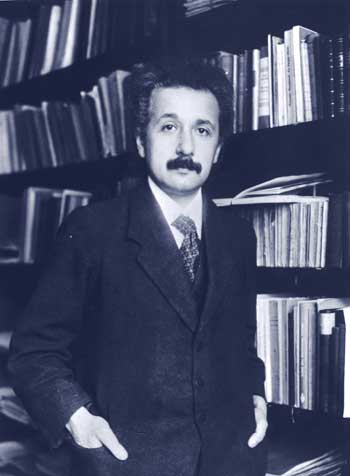

When he wrote that book, Heidegger was dissatisfied with the two dominant conceptions of time: Einsteinian and Bergsonian. For Heidegger, the two conceptions of time— “clock time” and “lived time”— one associated with Einstein and the other with Bergson, were symptomatic of the broader divisions of rationality and irrationality, where the first was associated with science and the second with experience.

Lived experience

Heidegger criticized both of these divisions, investigating their emergence. “ ‘The irrational’ also appears and, in its wake, ‘lived experience,’ ” he explained. These were strong words: “irrationality” thrived when “lived experience” was excluded from science.

Heidegger’s first confrontation with relativity theory occurred before he wrote Being and Time, while he was still a student in Freiburg. In his habilitation lecture, given in 1915, he confronted the theory of relativity directly, claiming that Einstein was not dealing with time but rather only with measurements of time. These two should not be confused.

Theory of relativity

“As a theory of physics, the theory of relativity is concerned with the problem of measuring time, not with time itself.” His judgment was severe, especially pointing out the limits of the theory: “The theory of relativity leaves the concept of time untouched,” he boldly concluded. Einstein erroneously assumed that time was a “homogenous, quantitatively determinable character”— which it was not, argued Heidegger.

The theory’s limited notion of time was the result of how it spatialized time, assuming it to be a homogenous and geometrical concept. Einstein, continued Heidegger, claimed that time “can be placed alongside three- dimensional space.” The philosopher disagreed with this point of view.

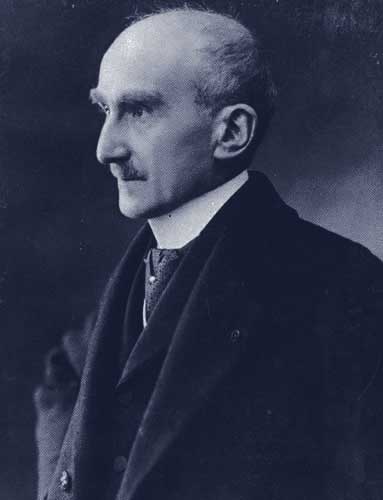

By treating time as space, scientists missed what Heidegger considered to be a much richer topic: an investigation into those aspects of time that could not be studied in the same way as space. Heidegger’s argument echoed Bergson’s own critique of measurement that had been advanced in Creative Evolution (1907).

The act of measuring time, according to both, destroyed much of it. “We, as it were, make a cut in the time scale, thereby destroying authentic time in its flow and allowing it to harden. The flow freezes, becomes a flat surface, and only as a flat surface can it be measured,” wrote Heidegger.

Simplistic notion of measurement

In his early work, Heidegger held certain views that were similar to Bergson’s, namely that the time of physicists referred to something other than that of the philosopher’s and that this time, was in essence, immeasurable. But as Heidegger’s thought developed, he would increasingly distance himself from any notions of Bergsonian time, even as he continued to sharpen his critique of Einstein.

The problem with Einstein’s work was that it was based on a simplistic and inadequate notion of measurement. Unless this notion was clarified, Einstein’s claim that he was dealing with real time remained suspect. To base a concept of time on measurements of time without noticing evident complexities in the concept of measurement itself was simply inadequate: “Any axiomatic for the physical technique of measurement must rest upon such investigations, and can never, for its own part tackle the problem of time as such.”

Theory of relativity

Heidegger did not argue for or against the validity of the theory of relativity. He instead expressed the need to think about “the problem of the measurement of time as treated in the theory of relativity.” Heidegger’s “The Concept of Time” lecture (originally 1924) diagnosed a damaging divide in the two dominant ways of thinking about time: the scientific notion of time and the lived notion.

In this short lecture, Heidegger explained how a renewed interest in the concept of time was largely due to Einstein: Interest in what time is has been reawakened in the present day by the development of research in physics. . . . The current state of this research is established in Einstein’s relativity theory.

The physicist, argued Heidegger once again, used clock time. And clock time, he repeated, was a grossly inadequate concept for understanding time: “Once time has been defined as clock time then there is no hope of ever arriving at its original meaning again,” he warned. The next summer, Heidegger gave a full course, “The History of the Concept of Time.”

His research was motivated by “the present crisis of the sciences,” which Heidegger blamed largely on Einstein: “In physics the revolution came by way of relativity theory,” he explained. Heidegger considered that most conceptions of time— including Einstein’s— derived from Aristotle’s: “Basically the concept of time as Aristotle conceived it is retained throughout.”

Heidegger’s project would differ from Aristotle’s, Einstein’s, and Bergson’s in this essential respect. Instead of continuing to debate about what time is, which was at the crux of the Einstein- Bergson debate, he proposed to take a step back and ask, what, after all, makes time? His stunning answer proposed that “human life does not happen in time but rather is time itself.”

Everydayness

Heidegger set out to do the contrary of what Einstein had done to time— in a radical way. Whereas the Aristotelian tradition from which Einstein drew (according to Heidegger) represented a culmination of a longstanding denial of differences between past and future, left and right, and up and down, for Heidegger these differences were now deemed essential.

https://amzn.to/2G0xGsa

In “everydayness,” he argued, they mattered substantially. Details as mundane and frequently overlooked as having something next to you or laying close to your dominant hand could have important consequences for what would happen next. They spoke volumes about the organization of the world. Even the future, ostensibly unknown to us, was primed to follow a certain course in connection to these frequently overlooked details.