Without doubt, the most bizarre and controversial event in the History of World War II was the parachute jump by Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess into Scotland on May 10, 1941. Hess was supposedly on a peace mission to negotiate a peace between England and Germany.

Hess was allegedly on his way to see the Duke of Hamilton in Scotland, with whom he believed he could negotiate a peace. As to why Hess thought that he could negotiate a peace in this way or why he thought that the Duke of Hamilton was the right person with whom to negotiate peace, this remains a mystery.

Explosive secrets

It is often said of Hess that he was kept in captivity because of what he might divulge if released. Yet if he had explosive secrets to reveal there were plenty of opportunities to make them known while still inside. He could have told Dr Seidl – when at length he agreed to see him. He could have told Albert Speer, probably closer to him than the others in the cell block, or any of his fellow prisoners, who could have released them to the outside world when they were freed.

Spandau

Their silence is evidence that he did not do so. Speer, who wrote of life in Spandau and of his experiences in the Third Reich, would certainly have used any revelations from Hess to boost sales.

Could Hess have been dissuaded from talking by threats of dire consequences for his family? Certainly, Ilse Hess thought that if he were allowed home he might open up.

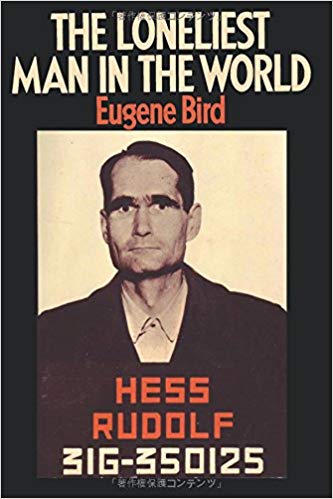

More profound questions concern the extent of his amnesia: how much he wanted to forget, how much he pretended to forget, how much he really had forgotten.This is illustrated by his replies to two men who had opportunity to probe him closely and who wrote books afterwards attempting to explain his mission and his character: the US director of Spandau, Colonel Eugene Bird. And after Bird retired, the French pastor, Charles Gabel.

Eugene Bird

In spring 1972 Bird’s talks with Hess came to an abrupt end. Bird was summoned to his commanding officer at US mission headquarters in Berlin and asked if he was responsible for a manuscript on Spandau written with Hess’s co-operation.

Bird agreed that he was. It was no secret among his colleagues; several of his fellow officers had read his chapters and made suggestions. Now it appeared that it had suddenly become a matter of grave official concern.

He was interrogated for several hours and when finally allowed home was placed under house arrest, and a team of officers searched every room and took away documents, letters and photographs.

His phone was tapped, and although allowed to travel in Berlin in his car he was followed by three cars, each containing two secret service men. Finally, he was asked to resign his post as US Commandant of Spandau, made to sign a secrets act and told he would have to await official permission before he could publish his book.

Flight to Scotland.

Of his flight to Scotland, Hess maintained an obdurate silence. In June 1986 as Gabel’s time in Spandau was coming to an end, the pastor reported, ‘He has told me nothing (of his flight) and will never tell anything. One must not expect revelations.

Yet Gabel had, unwittingly, recorded one important revelation: two years earlier, on 16 May 1984, Hess had neatly side-stepped the question of whether Hitler had sent him to Britain by referring to documents in London which remained closed to the public. ‘These,’ he told Gabel, ‘are without doubt the peace proposals I took. The English do not want it perceived that one could have stopped the war.

Hess made another reference to these documents in early 1987. His medical attendant, Abdallah Melaouhi, told him he had heard from one of the Soviet guards that the Russian leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, was prepared to release him on the next Soviet tour of duty at Spandau. Hess showed no reaction. Surprised, Melaouhi asked if he was not pleased by the news. Hess replied that if the Russians released him it would mean his death. ‘He would only be pleased if the British published his documents internationally.’

If they did so it would mean he could be freed; but Hess cautioned Melaouhi to say nothing about this. Melaouhi claimed that it was not until after Hess’s death that he understood what he had meant: that the British would never allow his release.

Delve deeper with Peter Padfield’s:

Hess, Hitler & Churchill: The Real Turning Point of the Second World War: A Secret History