The music of Jón Leifs is often inspired by Iceland’s powerful nature and literary heritage. From early on he was profoundly influenced by the medieval tradition of Icelandic literature, preserved in a handful of manuscripts, including the Poetic Edda and the Prose Edda.

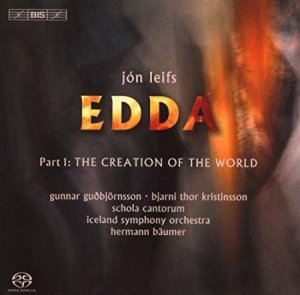

Leifs’ magnum opus is the Edda oratorio, a massive (although incomplete) work in three large parts which occupied him on and off for most of his composing career – from around 1930 to his death in 1968. A partial performance of Edda I – The Creation of the World – met with incomprehension, and Leifs only resumed work on his great project a decade later, completing the second part – The Lives of the Gods – in 1966.

He immediately started on the third part of the oratorio, and was still working on it at the time of his death. Neither of the two finished parts were performed in his lifetime, Edda I receiving its first complete performance in 2006 and Edda II in 2018, in conjunction with the recording of the present disc.

Leifs’ music is as ruggedly grandiose as its subject matter and the score calls for vocal soloists, choir and large orchestra, making huge demands on the performers. Once again the Iceland Symphony Orchestra and the intrepid Schola Cantorum join forces under the baton of conductor Hermann Bäumer, following up on their acclaimed recording of Edda I, which was described by reviewers as ‘one of the recording events of the year’ (Gramophone) and ‘splendid in its craggy and intensely individual lyricism and magnificence’ (MusicWeb-International).

Jón Leifs

Jón Leifs (1899–1968) was Iceland’s first nationalist composer. His music draws on the main types of Icelandic folk song and is often inspired by Iceland’s powerful nature and literary heritage. Largely neglected and ridiculed during his own lifetime, his music only began to receive wider notice in the decades following his death, and some of his works remain unperformed.

His magnum opus is the Edda oratorio, a massive (although incomplete) work in three large parts, which occupied him on and off for most of his composing career – from around 1930 to his death in 1968. From early on in his career, Jón Leifs was profoundly influenced by the medieval tradition of Icelandic literature.

Poems about Odin and other gods

Much of the poetry of medieval Iceland is preserved in a handful of manuscripts written in the thirteenth century, although the material is believed to be older. Poems about Odin and other gods, and about the major characters in the heroic story of the Völsungs, are transmitted in an anthology known as Codex Regius (The King’s Book), written about 1270 and traditionally referred to in English as the Poetic Edda.

Another substantial and slightly older text is the Prose Edda (or Snorra Edda, as it is known in Icelandic), believed to have been written around 1225 by the chieftain Snorri Sturluson. This work combines a treatise on poetry with an account of the myths and legends also contained in the Poetic Edda. These texts form the basis of the oratorio Edda for soloists, choir and orchestra.

When he first began contemplating the work, in 1928, he had intended to set only Völuspá (The Seeress’s Prophecy) which is one of the great Eddic poems, a monologue of roughly 60 stanzas in which a sibyl describes a vision of the world’s beginning and collapse – the apocalyptic carnage of ragnarök, in which many of the gods die and the world is sub merged in water.

Still, destruction is followed by re-creation: the earth rises from the sea again, and a new generation of gods takes over. The dimensions of the work far outgrew the composer’s initial plan.

By 1930, he was referring to an ‘Edda-oratorio’, the libretto to which he himself had begun to assemble from various Eddic sources. When the oratorio text was complete in May 1933, it consisted of 350 stanzas and ran to 86 typewritten pages.

The work was to be divided into four parts:

- The Creation of the World (Sköpun heimsins),

- The Lives of the Gods (Líf guðanna),

- Twilight of the Gods (Ragnarökr), and

- Resurrection (Endurreisn).

By using the Norse myths as a basis of a tetralogy, Jón Leifs was of course inviting comparisons with Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung, with which he was well acquainted. Karl Muck’s conducting of Siegfried at the 1920 Munich Summer Festival had left a strong impression, and he had studied the score during his years at the Leipzig Conservatory.

A protest against Wagner

But he found Wagner’s approach too romantic and sentimental for the subject matter, and claimed to have written many of his own works, including the Edda oratorio and the Saga Symphony, as ‘a protest against Wagner, who misunderstood so terribly the Nordic character and Nordic artistic heritage’.

In contrast to Wagner, Jón Leifs used the original text (in Icelandic) and his oratorio setting consists largely of static tableaux rather than a dramatic retelling, at least in parts I (depicting natural phenomena, a Leifs hallmark) and II (describing the Gods and their habitat). Jón Leifs completed Edda I in 1939, but did not immediately continue with the project.

Performances of Edda I proved impossible to procure, and Leifs instead spent several years writing the ‘choreographic drama’ Baldr, itself also based on the ancient mythology. He began composing Edda II in 1951, but soon the project stalled. Two movements from Edda I were premièred at the Nordic Music Days in Copenhagen in 1952 but were poorly received, and this, along with the harsh criticism of his Saga Symphony in Helsinki two years earlier, dealt the composer’s self-confidence a severe blow.

He only revisited the score to Edda II a decade later. In fact, Jón Leifs only hit his stride with Edda II in early 1966, completing the final four movements between January and May. He had originally intended the first movement to be titled Gods (Æsir), a portrayal of each of the male gods in turn (Odin, Thor, Baldr etc.). He later decided to divide it into two movements: the first (Odin) depicts the father of all the gods; the second enumerates his sons (Sons of Odin) and is referred to in one sketch as a ‘Scherzo with trio episodes’.

Otherwordly

A noticeable feature of the first movement is the marking ‘quasi jodeln’ (‘as if yodelling’) in the tenor solo, presumably to give these lines an exotic, even otherworldy, character. The calmer third movement, Goddesses (Ásynjur), is a port rayal of the female characters: Frigg, Freyja, Sigyn etc. The oratorioʼs last three movements (Valkyries, Norns and Warriors) are far shorter than the previous ones, perhaps an indication that Leifs suspected time was running out and that he was determined to finish the work.

Jón Leifs immediately began work on the next instalment. Edda III – Twilight of the Gods calls for mammoth performing forces, a decision inspired in part by hearing what he later described as ‘two of the most magnificent Requiems ever written’ – by Berlioz and Verdi – in Paris in November that year. On All Souls’ Day, he heard the Berlioz Requiem performed at the Panthéon by the ORTF Philharmonic and the fanfare band of the Garde républicaine.

The Verdi Requiem was given at Saint-Roch three days later. The dramatic qualities of both works, as well as the vast resources of the former, inspired him to make the single-movement Edda III his most demanding work by far. Virtually no sketches exist for Edda III; it is as if the composer, sensing that time was running out, wrote most of his ideas directly into the full score.

I’ve never done anything like it before

In an interview he remarked that ‘I’ve never done anything like it before. It’s impossible to describe such events without em ploying gigantic forces.’ While composing Edda I, Jón Leifs often remarked on his fear of dying before achiev ing his life’s goals as an artist. In 1932, the death and funeral in Leipzig of the poet Jóhann Jónsson had a profound effect on him and he confessed to his sister his terror of ‘meeting the same fate, before I complete my main works’.

A premature death was still on his mind a year later: ‘My main concern is that I will not live to complete the works I must finish, and that no one else can accomplish. Everything else seems to me trivial in comparison.’

It is almost as if he sensed his own fate, for while Leifs did not die young, his epic Edda project was doomed to remain incomplete. In April 1968 he began vomiting blood and he was admitted to the Reykjavík City Hospital on 14th May, where doctors discovered a malignant tumour.

In response, he briefly put aside Edda III to express more tender emotions in a simple, touching work for string orchestra, Consolation, Op. 66. He then returned to Edda III once more, completing page 200 of the full score at the hospital on 5th June 1968, the day before undergoing an operation.

Baldur the white god

He managed to write twelve more pages before his powers were exhausted. Edda III remained incomplete, and to this day has never been performed. Only a libretto draft hints at Jón Leifs’ intentions for the final instalment, Edda IV, in which a green and fair earth rises from the ocean and a new world order is established under the leadership of Baldur, the ‘white god’.

The present recording was made following the première performance of Edda II in Reykjavík in March 2018. It is the thirteenth volume in the ongoing Jón Leifs Edition on BIS, and presently only two of Leifs’s large-scale works for chorus and orchestra remain unperformed: Darraðarljóð (Song of Dorrud) from 1964 and the incomplete Edda III, of which roughly an hour’s worth of music exists.

Árni Heimir Ingólfsson 2018