In the waning hours of New Year’s Eve 1944, the Wehrmacht launched Operation Nordwind, the last German offensive of World War II in the west. It was an attempt to exploit the disruptions caused by the Ardennes offensive further north in Belgium.

When Patton’s Third Army shifted two of its corps to relieve Bastogne, the neighboring Seventh US Army was forced to extend its front lines. This presented the Wehrmacht with a rare opportunity to mass its forces against weakened Allied defenses. At stake was Alsace, a border region that had been a bone of contention between France and Germany for the past century. Taken from France by Germany in the wake of the 1870 Franco-Prussian war, it returned to France after World War I in 1918, only to be retaken by Germany after France’s 1940 defeat.

The fate of Alsace was of no particular concern to Eisenhower and the Anglo-American forces in north-west Europe, and the initial plans were simply to withdraw the Seventh US Army to more defensible positions in the Vosges mountains until the more crucial Ardennes contest was settled. However, the forfeit of the Alsatian capital of Strasbourg was completely unacceptable to de Gaulle and the Free French forces, resulting in a political firestorm that forced a reconsideration of Allied plans for dealing with the German attacks.

Hitler saw Alsace as the last tangible reminder of Germany’s great victory in 1940 and Strasbourg was the symbol of German control on the west bank of the Rhine; he insisted the city be retaken. The failure of the Ardennes offensive convinced Hitler that some new tactic had to be employed when dealing with the Allies. Instead of a single large offensive, Hitler decided to launch a series of smaller, sequential offensives. As a result, some German commanders called the Alsace campaign the “Sylwester offensives” after the central-European name for the New Year’s Eve celebrations.

The initial Nordwind offensive emanated out of the fortified border city of Bitche, but made little progress in the face of stiff American resistance. The American battle cry became “No Bulge at Bitche!” US units were pulled off the Rhine near the Strasbourg area to reinforce the Bitche sector, providing the local German commanders with another temporary opportunity.

Operation Nordwind

A hasty river-crossing operation was staged at Gambsheim and the bridgehead gradually expanded in the face of weak American opposition. In view of the failure of the initial Nordwind offensive around Bitche, Hitler shifted the focus of the Alsace operation farther east towards Hagenau, attempting to link up the two attack forces and push the US Army away from the Rhine. This led to a series of extremely violent tank battles in the middle of January around the towns of Hatten-Rittershoffen and Herrlisheim, which exhausted both sides. An experienced German Panzer commander later called these winter battles the fiercest ever fought on the Western Front.

When the Red Army launched its long-delayed offensive into central Germany on January 14, the possibilities for further Wehrmacht offensives in Alsace drew to an end. Panzer units were transferred to the Eastern Front, and German infantry units began to establish defensive positions. With the Wehrmacht exhausted and weakened, it was the Allied turn for action.

A large pocket of German troops was trapped on the west bank of the Rhine around Colmar, and Eisenhower insisted that the Colmar Pocket be eradicated. The 1ère Armée did not have the strength to do it quickly, so in late January, additional American divisions were moved into Alsace from the Ardennes front. In two weeks of fierce winter fighting, the German Nineteenth Army was decisively defeated and its survivors retreated over the Rhine.

The January 1945 Alsace campaign fatally damaged one German field army and severely weakened a second. This became startlingly clear in March 1945 when the US Army’s lightning campaign crushed Heeresgruppe G (Army Group G) in the Saar-Palatinate, later dubbed the “Rhine Rat Race.” The obliteration of the Wehrmacht’s exhausted southern field armies was the root cause of Patton’s dramatic advance through southern Germany in April and May 1945.

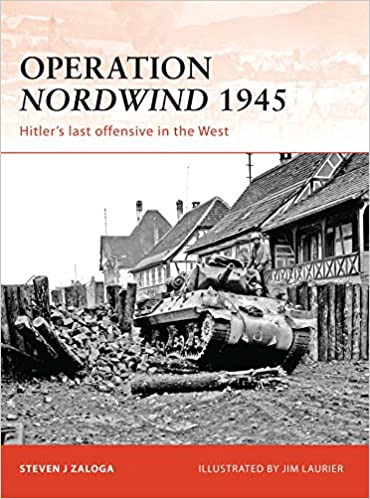

src. Steven Zaloga. Operation Nordwind

His book contains several excellent photographs and has excellent maps to highlight the story.

Steven J. Zaloga received his BA in history from Union College and his MA from Columbia University. He has worked as an analyst in the aerospace industry for over two decades, covering missile systems and the international arms trade, and has served with the Institute for Defense Analyses, a federal think-tank.

He is the author of numerous books on military technology and military history, with an accent on the US Army in World War II as well as Russia and the former Soviet Union. The author lives in Abingdon, Maryland. The author lives in Abingdon, MD.