Here is a subconscious double standard: Infinities of time seem a little different from infinities of space. It is natural to think that space extends out in all directions forever (or is this a culturally instilled belief?). Time is supposed to be infinite only in the future direction. We ask when time began but rarely where space began.

The infinity of past time

The infinity of past time is an unpopular belief. Yet it would “answer” questions of when or how the world was created by throwing them out as meaningless. In contrast, the infinity of future time appears to be universally accepted, even by those religions that postulate an apocalypse in the meaning of end-time. After the millennium, the good live on forever, or the cycle starts over with a new creation. Few if any doctrines are nihilistic enough to believe in a real end to time, where things revert to exactly the same nonexistence as before the beginning of time, only this time for good.

https://amzn.to/2UyfHi3

Paradox of Tristram Shandy

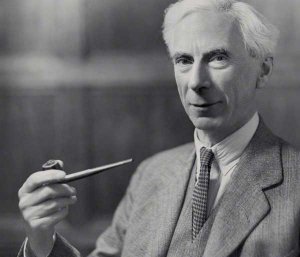

Bertrand Russell’s “paradox of Tristram Shandy” plays with the idea of an infinite future. Tristram Shandy is the narrator of Laurence Sterne’s rambling novel of the 1760s, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. Russell wrote: “Tristram Shandy, as we know, took two years writing the history of the first two days of his life, and lamented that, at this rate, material would accumulate faster than he could deal with it, so that he could never come to an end. Now I maintain that, if he had lived for ever, and not wearied of his task, then, even if his life had continued as eventfully as it began, no part of his biography would have remained unwritten.”

Russell’s reasoning goes like this: Say that Shandy was born on January 1, 1700, and began writing on January 1, 1720. The first year of writing, 1720, covers that first day, January 1, 1700. The progress would go like this:

| Year of Writing | Covers Events of | |

| 1720 | January 1, 1700 | |

| 1721 | January 2, 1700 | |

| 1722 | January 3, 1700 | |

| 1723 | January 4, 1700 | |

| … | … | |

| etc. | etc. |

There is a year for every day, and a day for every year. Were Shandy still writing in 2085, he would be up to the events of December 1700. In turn, this immortal Shandy would get to setting down today’s events circa the year 115705 something. You cannot single out a day for which it isn’t possible to schedule a future year for recording its events. Therefore, said Russell, “no part of his biography would have remained unwritten.” Even so, Shandy gets further and further behind in his writing. With every year of writing he falls 364 years further from completion!

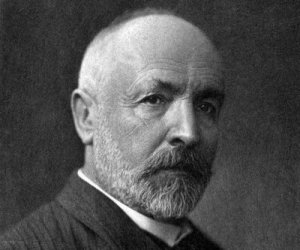

Theory of infinite numbers

Russell’s reasoning was based on Georg Cantor’s theory of infinite numbers. If two infinite quantities can be placed in one-to-one correspondence to each other, they are equal. For instance, mathematicians hold that the number of whole numbers (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 …) equals the number of even numbers (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 …)—rather than being twice as much, as you might think. The two are equal because every whole number n can be paired with one even number 2n, and the pairing will leave no even numbers left over.

More mind-bending is a reversal of the paradox. Suppose that there is an infinity of past time, and that Shandy has already been writing for an eternity. Then there is the same “Cantorian” correspondence between years and days. Shandy would have just finished the last page of his autobiography. But that’s ridiculous. How could Shandy have chronicled yesterday’s events already, when it should have taken him a whole year?

Reverse paradox

Many have used the reverse paradox to demonstrate, not very convincingly, the impossibility of a past eternity. A reasonable resolution of the reverse Tristram Shandy paradox was supplied by Robin Small. It is, in fact, impossible to establish a correspondence between specific days and specific years.

Pretend it is midnight, December 31, 1988, and Shandy has just finished the last page of his manuscript. What day has Shandy been writing about this past year? It can’t have been any day of this year. (Otherwise he would have spent the early part of the year writing about a day that hadn’t happened yet.) The most recent day he could have been writing about in 1988 is December 31, 1987.

If indeed Shandy spent 1988 recounting December 31, 1987, then he must have spent 1987 writing about December 30, 1987. That again is impossible. Actually, Shandy couldn’t have written about any day later than December 31, 1986, in 1987.

But if he wrote about December 31, 1986, in 1987, he would have had to write about December 30, 1986, in 1986 … Any proposed correspondence crumbles beneath our feet. The alleged day Shandy has been writing about recedes into the infinite past. There is no way of singling out any day.

Conclusion

Conclusion: If there is an eternity of past time, and Shandy has been writing since the “beginning”, he will have an infinitely long unfinished manuscript. The most recently completed page will describe events of the infinitely remote past.

Russell does not claim that Shandy will “ever” finish the manuscript. Rather, no specific day you can mention goes unrecorded. Tristram Shandy’s “last” page is forever a mirage.