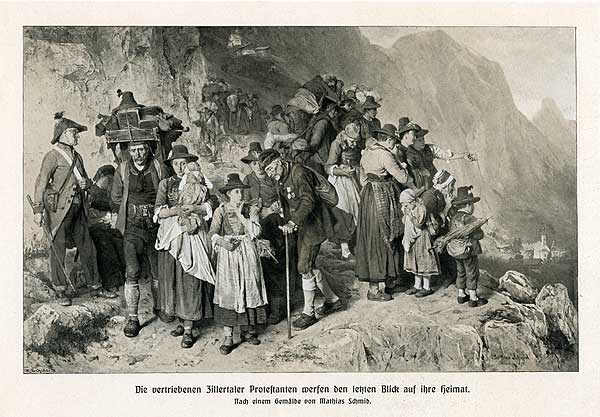

The tendency to deprecate the religious other through systematic attribution of Satanism survived the fragmentation of Western christianity during the Reformation schisms in the early modern period. Catholic polemicists deployed old stereotypes about Satanist heretics against Protestant Christians, while Protestants accused the Roman Catholic Church of demonic idolatry and proclaimed the Roman pope to be a servant of Satan.

A new sect

Indeed, it was to be exactly during this period that fears about a conspiracy of devil worshippers would reach a historical apogee. Rumors of a widespread cult of Satan increased to alarming intensity in parts of the Western world as contemporary authors started to speak about a new, ultramalicious “sectam modernum” that sought to overthrow Christendom from within.

Blasphemous rites

Blasphemous rites

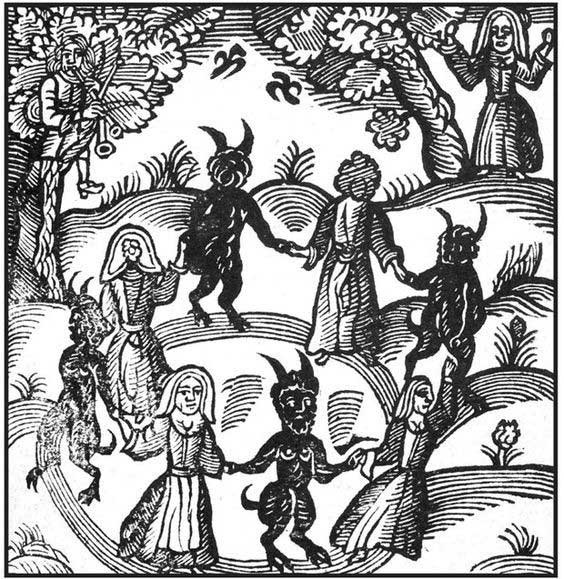

Its adherents could be found in all segments of society, but particularly among women. They allegedly used magic to inflict harm on good Christians and convened in isolated and far- away places such as mountaintops.

There they performed atrocities and blasphemous rites and eventually ended up having sex with the devil and each other.

Contrary to popular opinion, hunting witches was not the exclusive preserve of the Roman Catholic Church— and much less of the Roman and Spanish Inquisitions, which were in fact rather lenient toward those accused of witchcraft.

Rather, it was an activity in which the secular authorities, Protestant as well as Roman Catholic, enthusiastically shared. In fact, belief in witchcraft and maleficium had long predated Christianity.

Maleficium

In fact, belief in witchcraft and maleficium had long predated Christianity. The power to ward off demons and harmful cosmic forces (by naming them properly and using apt rituals) assume the ability to exert a certain measure of control over them.

This left open the possibility of its mirror image as well: directing these demons or cosmic forces to bring misfortune on those to whom one was for whatever reason unfavorably disposed. This practice, and the fear of it, has been documented from very early times.

Pagan Romans

Pagan Romans

The pagan Romans already considered maleficium to be an exceptionally horrendous crime for which they reserved one of their harshest legal sanctions: being burned alive. Initially, the coming of Christianity had not necessarily meant bad news for those accused of witchcraft.

Charlemagne’s new law for his Saxon territories, for instance, forbade the heathen Saxons to eat witches— apparently the customary retribution for the magic cannibalism that witches were supposed to practice.

Theological considerations also made ecclesiastical authorities skeptical about certain popular conceptions regarding maleficium. Incidentally, Charlemagne also decreed that those found guilty of sorcery “should be turned over to the Church as slaves, while those who sacrificed to the Devil (i.e., the Germanic gods) should be killed”. src Richard Kieckhefer, Magic in the Middle Ages.

Powerful Demons

Powerful Demons

Although Satan and his demons were extremely powerful, official theology maintained that, as angels, they were essentially spirits and thus unable to change material reality. Their influence extended itself exclusively through manipulation of the human psyche by way of sinful suggestions, illusions, and possession. Deliberations like these seem to have formed the background for the well- known Canon Episcopi, a directive for tenth- century bishops that already mentions women who claim to go on night rides with Diana or Herodias.

The text of the Canon Episcopi makes it quite clear that the nightly activities of these women were thought to be mere delusions: the real sin was to believe in the reality of these fantasies.

Jews and heretics

Jews and heretics

This did not prevent belief in the danger of maleficium from being widespread in the Middle Ages.

Nor was it solely the preserve of the uneducated or rural populace, as is shown by the frequent scandals evolving maleficium that erupted at the courts of Christian monarchs from the fourth up to the eighteenth centuries. The crucial step that made possible the massive witchcraft persecutions of the early modern era was the application of the Satanist stereotype that had been developed about Jews and heretics to the practice of sorcery.

Manicheans

There were some starting points for this in the earlier propaganda against the religious other. Already in Antiquity, as we have seen, the Manicheans were suspected of practicing maleficium, a suspicion sometimes extended to other heretic groups.

Jews enjoyed a similar reputation as sorcerers in the popular and learned imagination.

Toward the end of the Middle Ages, the reverse step was also made in some places: that of regarding sorcerers as members of a heretical organization. During the fourteenth century, the Papacy formally declared demonic magic heresy and veneration of Satan.

Sectarian witchcraft

Toward 1400, the first trials for sectarian witchcraft— that is, witchcraft allegedly practiced in an organised sect, rather than by an individual— were held in the Savoyard Alps.

Research by notable witchcraft historians has shown this occurrence to be directly related to the Inquisition persecution of Waldensians just a few decades earlier, during which the inquisitors had transformed the Waldensians into a sect of devil- worshipping sorcerers who convened at secret sabbats.

This demonizing effort was evidently successful. In certain parts of Europe, the designation “valdesia” or “vauderie” (Waldensianism) grew not only into a general brand name for heresy, but also into a familiar synonym for witchcraft.

https://amzn.to/2ZI7JXx

Organized Satanists

The idea of an organized Satanist witchcraft thus was neither traditional nor popular. On the contrary, it was developed by an educated elite and propagated by those who were able to participate in the most recent scholarly insights. The postulation of a heretic, devil-worshipping conspiracy behind the practice of sorcery also had important practical implications.

Inquisitorial judicial procedures could now be used in the persecution of maleficium, whereas beforehand convictions of maleficium could only occur after somebody who was “damaged” by the perpetrator had laid charges against him or her and managed to prove them.

Because of its character as a crimen exceptum, torture could legally be used to extract confessions; because of the presumed collective nature of witchcraft, legal authorities tended to search for accomplices.

This combination could easily lead to an epidemic of witchcraft prosecutions. Through their sheer scale, the witchcraft persecutions also indicate the further strengthening of central, nonlocal forms of authority that had taken place in Western Europe.