Tertön Sogyal’s story. In the mid-19th century, the life of a horse-riding bandit in the eastern Tibetan region of Kham took a drastic turn that would alter the future of Tibetan Buddhism. After the young man rejected his father’s demands to lead a life that was harming others, he placed his trust in wise hermits and learned monks who nurtured his spiritual development in remote caves and sacred temples.

As his mind turned away from worldly pursuits and toward the Buddha’s instructions on how to develop boundless compassion and recognize one’s inherent enlightened potential, he began a series of meditation retreats that would last more than a decade.

By perfecting his meditation skills, he realized the most profound Buddhist teachings. And soon a treasure-house of visions and spiritual revelations burst forth from his wisdom mind. He became the tantric yogi par excellence. Eventually, the Thirteenth Dalai Lama asked him to become his guru, and to use his spiritual revelations to defend Tibet. This yogi’s name was Tertön Sogyal.

Tertön Sogyal’s emergence as a powerful spiritual figure came at a time when geopolitical pressures were pressuring Tibet and threatening the life of the Dalai Lama. Outside powers—British India, the Qing dynasty, and Tsarist Russia—were vying for control of the Buddhist country.

Tibet’s army in Lhasa, with only muskets and lances, and the decentralized tribes of eastern Tibet, with few rifles, would be no match for foreign militaries. Yet even more dangerous than Tibet’s imperial neighbors was the internal strife that Tertön Sogyal witnessed among Tibetan Buddhists and between civil leaders in Lhasa.

Religious sectarianism was rife among some influential monasteries and abbots. Cronyism and the use of funds for personal gain were prevalent. The spiritual corrosion was weakening Tibet, making the country ever more vulnerable to attacks by outside forces.

Padmasambhava had predicted that trouble would arise for Tibet at the end of the 19th century. When the Indian guru established Buddhism in Tibet in the 8th century, he had made prophecies about the age of degeneration—kaliyuga—when disturbing mental states such as desire, anger, pride, and jealousy would preoccupy the minds of Tibetans and lead to conflict and wars.

This degenerative period would bring an overall deterioration in the quality of all things, from the sharp acumen of people to the nutritional content of food. Among the monks and lay tantric practitioners in Tibet, Padmasambhava predicted erosion in the strength of religious vows and precepts—even to the point of contravening the guidance of spiritual teachers. This degeneration, and the self-cherishing attitudes behind it, was the source of Tibet’s suffering in the 19th century.

But there were antidotes to this degenerative time that could resuscitate spiritual practitioners and maintain Tibet as a realm where Buddhism could flourish. These antidotes would appear in the form of Padmasambhava’s spiritual teachings. He concealed these antidotes as “treasures”—terma—in the form of texts describing liturgies, religious practices, and advice, sealing them with the intent that they be revealed when they would be most needed. Padmasambhava presaged future yogis to be tertöns, the revealers of his hidden treasures.

One after another, the tertöns appeared throughout Tibet’s history, becoming a garland of precious adornments for the Buddha Dharma, the teachings of Buddhism. And at the turn of the 20th century, after the passing of two great tertöns and spiritual luminaries in Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo and Jamgön Kongtrul, Tertön Sogyal was considered to be the most significant tertön. This was because the treasures he was revealing were specifically tailored by Padmasambhava to protect the Buddhist teachings, to defend Tibet against foreign invasions, and to guard the life of Tibet’s spiritual and political ruler, the Dalai Lama.

Tertön Sogyal’s spiritual revelations have a timeless quality and speak directly to the meditator in solitary retreat or to those engaged in the pursuit of positive social change. His teachings are as relevant and as much needed today as when the tertön first revealed them in the highlands of Tibet. And Tertön Sogyal’s own life of overcoming seemingly insurmountable obstacles is an inspiring model of how to integrate skillfully the wisdom gleaned from spiritual practice with the compassionate wish to benefit all sentient beings. “Fearless in Tibet” is the life of a Tibetan mystic. It is the story of Tertön Sogyal.

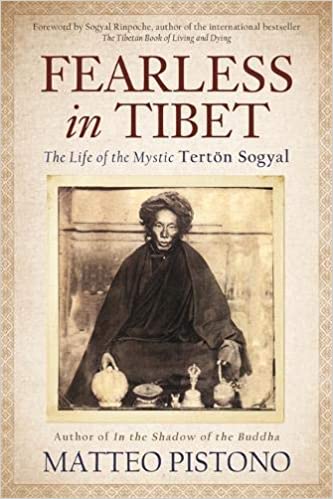

The narrative in Fearless in Tibet is Matteo Pistono chronicle of the life of Tertön Sogyal based on a number of authoritative sources. His primary source was Tulku Tsultrim Zangpo’s (Tsullo’s) lengthy spiritual biography of Tertön Sogyal that was carved onto woodblocks in the 1940s, about 15 years after Tertön Sogyal’s passing. Entitled The Marvelous Garland of White Lotuses, it is the only known biography and is based upon mystical prophecies about Tertön Sogyal by Padmasambhava and other saintly persons. Little in the way of history in a Western sense exists in Tsullo’s traditional hagiography, though when one reads it alongside other historical sources—Tibetan, Chinese, and Western, some of which are in Pistono’s book Reference section—it is clear that Tertön Sogyal’s mystical visions and spiritual revelations occurred during very specific episodes in the tumultuous political times in late 19th- and early 20th-century Tibet.

src. Matteo Pistono

Delve deeper with: Fearless in Tibet: The Life of the Mystic Terton Sogyal