The memory of the Rhine Meadow Camps, where thousands of German soldiers were held as prisoners by the Western Allies after World War II, remains disturbingly absent in Germany’s collective memory. This omission is not just a matter of historical oversight; it reflects deeper political motivations and the reluctance of mainstream historians to confront uncomfortable truths.

For decades, the fate of German POWs in these camps was a subject of little interest. Historical memory, after all, is often shaped by contemporary political needs. In ancient Rome, the practice of damnatio memoriae sought to erase unpleasant events from public memory. Similarly, post-war Germany, aligned with the Western bloc, focused on Soviet crimes while downplaying or ignoring human rights abuses committed by the United States, France, and Great Britain. The suffering of German POWs did not fit the narrative of the time, and so it was largely erased from public discourse.

It’s curious that even after the war, in a supposedly free and open society, institutional historians often attacked those who ventured into these sensitive topics as outsiders. When these non-traditional historians reached conclusions that clashed with established narratives, they were often met with fierce criticism. Prominent examples include Joachim Fest and Sebastian Haffner, whose works challenged mainstream views on Germany’s history.

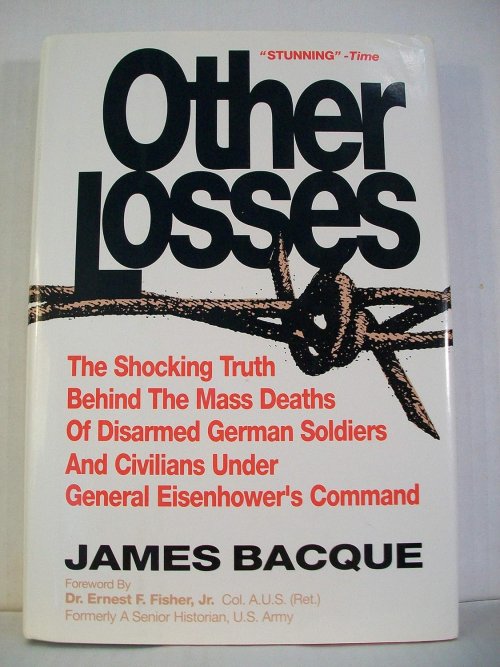

Breaking the Silence: James Bacque’s Revelations

The silence surrounding the Rhine Meadow Camps was shattered in 1989 when Canadian journalist and historian James Bacque published Other Losses. Bacque’s research suggested that up to one million German prisoners may have died in these camps due to deliberate neglect by the Western Allies. His book, released in Germany under the title Der geplante Tod (The Planned Death), quickly became a sensation.

Bacque’s thesis—that the Americans and French had deliberately allowed hundreds of thousands of Germans to die by withholding food and rejecting aid from organizations like the International Red Cross—challenged the long-held narrative of the Western Allies as liberators and protectors against the Communist East. The media and academic community swiftly condemned Bacque’s work, dismissing his findings as exaggerated. Yet, despite the backlash, Bacque had opened a Pandora’s box, forcing historians and the public alike to reconsider this dark chapter of post-war history.

The Battle Over Historical Truth

In response to Bacque’s controversial claims, the historical community rallied to discredit his work. Despite his meticulous research, which included archives from several countries, Bacque was criticized for his methodology and conclusions. Some historians argued that the chaos and shortages of the post-war period, rather than any deliberate malice, were to blame for the deaths in the camps. Yet, even as they challenged Bacque’s numbers, these historians could not completely dismiss his findings.

The Eisenhower Center in New Orleans, named after the general-turned-president whom Bacque accused of orchestrating these atrocities, held a symposium in 1990 aimed at debunking Bacque’s work. However, the historians involved struggled to disprove his findings definitively. Ironically, the center’s founder, Stephen E. Ambrose, later faced severe criticism for his own scholarly practices, including accusations of plagiarism and a lack of scientific rigor.

Reassessing the Past

Bacque’s work also caught the attention of Peter Worthington, founder of the Ottawa Sun, who supported Bacque’s claims in a 1989 column. Worthington argued that Eisenhower’s policies had resulted in more German deaths in peace than on the battlefield, calling into question long-held assumptions about the post-war period.

German historians, however, were less supportive. Their research often cited lower figures for the number of prisoners and deaths, but they too struggled to provide clear answers. Even the standard documentation, compiled by Erich Maschke, which lists millions of German POWs, leaves many questions unanswered. Critics of Bacque accused him of irresponsibility for suggesting that up to one million of these deaths could be attributed to the Rhine camps. Yet, in the absence of reliable data, such accusations seemed more like an attempt to protect established narratives than to uncover the truth.

A War Crime in the Shadows

Arthur L. Smith, in his book The “Missing Million”, attempted to discredit Bacque’s findings, but in doing so, he inadvertently supported some of Bacque’s conclusions. Smith acknowledged the complexity and contradictions in the documents from the period, and even described the treatment of German POWs in the Rhine camps as a “shameful chapter” in the history of the post-war era. He concluded that what happened in these camps was indeed a war crime, although he argued that the blame should not rest solely on the American soldiers on the ground, but also on their commanders and the policymakers who failed to intervene.

Smith’s recognition of the atrocities committed in the Rhine camps is a step toward acknowledging this dark chapter of history. However, he also pointed out that the German prisoners had no authority to turn to for help, as the German states were only reestablished after the camps had been dissolved. This fact underscores the helplessness of the prisoners and the extent to which their suffering has been overlooked in the broader narrative of World War II and its aftermath.

Unveiling the Hidden Tragedy

The story of the Rhine Meadow Camps, as explored by James Bacque and brought to public attention despite widespread resistance, is a reminder of how historical narratives are shaped by those in power. Bacque’s work, though controversial, forced a reevaluation of the post-war period and the treatment of German prisoners. It highlights the importance of questioning established histories and the need for a more nuanced understanding of the past—one that acknowledges the suffering of all victims, regardless of which side of the conflict they were on.

Hans Jürgen Wünschel’s original article in Compact Geschichte Nr. 20 provides a valuable perspective on this forgotten chapter of history, challenging us to confront uncomfortable truths and broaden our understanding of World War II’s legacy.

Quotes

“Germany is not occupied for the purpose of its liberation, but as a defeated enemy state.”

(US Directive JCS 1067, which outlined the principles of American occupation policy; effective until July 1947)

“The military government has requested me to announce that under no circumstances may food be collected from the population to be delivered to German prisoners of war. Anyone who violates this order and, if necessary, bypasses the security barriers to provide the prisoners with something, risks being shot.”

(Letter from the President of Koblenz to the District Administrator of Bad Kreuznach, May 9, 1945)

“Farmer Karl Schneider from Sinzig sometimes finds the identification tags of German soldiers while plowing his fields on the former camp grounds. To this day, no one has investigated the pits of the former ‘toilet facilities’ for the remains of missing German Wehrmacht soldiers.”

(Helmuth Euler, The Decisive Battle on the Rhine and Ruhr 1945, 1981)

“The number of victims is undoubtedly more than 800,000, almost certainly more than 900,000, and quite probably more than a million. The causes of their deaths were deliberately created by army officers who had sufficient food and other resources to keep the prisoners alive. Aid organizations that tried to help the prisoners in the American camps were denied permission by the army.”

(James Bacque, Other Losses, 1989)

“The book by Canadian author James Bacque Other Losses first appeared in 1989. (…) Patriotic feelings are stimulated, in a whining tone alleged crimes are revealed, stirring German emotions over supposedly unjust persecution.”

(Historian Wolfgang Benz in the documentation Prisoner of War Camps 1939-1950 by the State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate, 2012)

“The prisoners in the Rhine Meadow Camps suffered from hunger in the first months, some of them only receiving their first bread after weeks. They also ate various plants they found in the camp. (…) The supply of drinking water was also insufficient, and the prisoners had to stand in line for hours to get heavily chlorinated water — the American camp administration tried to prevent the spread of disease in this way.”

(Pages to the Land No. 63: Prisoner of War Camps in the Rhine Meadow Camps 1945-1948, State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate, 2015)

“When asked by the Wall Street Journal whether excursions to concentration camps were appropriate, [then AfD leader Frauke] Petry said: ‘It is important for students to understand what humans can do to each other,’ and then she continued, ‘However, they should also be informed that Americans allowed German prisoners of war to starve in the Rhine Meadow Camps after World War II.'”

(Stern, March 3, 2017)

“The now 94-year-old Rolf Sachweh survived the ordeal. To this day, he cannot forget the images of suffering from that time. Even the makeshift latrines became a death trap for some of the emaciated prisoners: ‘They sometimes fell into the filth and stayed there. They flailed a few times and then were gone. No one helped them. I still can’t bear to think about it.'”

(SWR, May 7, 2020)

“The CDU state parliament member from Bad Kreuznach, Dr. Helmut Martin, is calling for more funds to expand the ‘Field of Sorrow’ memorial near Bretzenheim. (…) The memorial, located on the federal highway between Bretzenheim and Bad Kreuznach, commemorates the Rhine Meadow Camp near Bretzenheim, which at its peak housed 110,000 prisoners.”

(Antenne Bad Kreuznach, March 31, 2022)

“Many German prisoners of war suffered from hunger and cold in the Rhine Meadow Camps in 1945. Right-wing radicals claim that the Allies deliberately let one million people die there. This legend has long been debunked.”

(Spiegel, July 4, 2022)

“For years, right-wing extremists have invoked the myth of the Rhine Meadow Camps to reverse the roles of perpetrator and victim. Now, esoteric revisionists and QAnon followers are picking up the thread — to ‘heal the German soul’ in the Ahr Valley.”

(Belltower News, May 31, 2023)

Source “Die Todeslager der Amerikaner” – COMPACTGeschichte Nr. 20