In the harrowing depths of history, certain events are etched with such darkness that they transcend the boundaries of time, becoming a relentless reminder of human suffering. The tragic tale of Breslau and East Prussia during the final months of World War II is one such chapter—a narrative of terror, desolation, and unimaginable human cruelty. In the Maier Files series, particularly in Episode X, Rolf Dietrich’s journey to Breslau to find his beloved, Frau Buechler, is a poignant thread that ties into this grim historical tapestry. It is through these stories that the horrors of the past are brought to life, compelling us to confront the uncomfortable truths of our shared history.

The Exodus from Breslau: A Descent into Hell

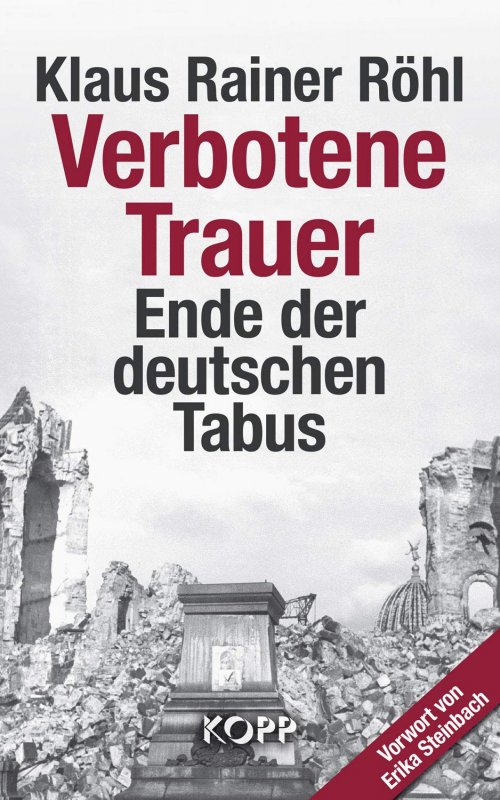

The city of Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland) in January 1945 was a place where the ordinary became extraordinary in the most horrific sense. As the Red Army advanced, the citizens of Breslau were caught in a desperate exodus. Klaus Rainer Röhl, in his eye-opening book “Verbotene Trauer” (Forbidden Mourning), recounts the gut-wrenching experiences of those who fled, as well as those who were left behind to face the wrath of war. Röhl’s narrative, drawn from eyewitness accounts, unveils the unimaginable suffering endured by civilians, particularly women and children.

Hedwig Rosemann, a resident of Breslau, was among those forced to leave their homes on January 22, 1945. With only two hours to prepare, she fled to Löwenberg (now Lwówek Śląski) with her family, seeking refuge with relatives. However, safety was elusive. By February 13, 1945, the situation had deteriorated further as the Red Army closed in. The roads were choked with fleeing civilians, rendering escape impossible. As battles raged on February 14-15, Rosemann and her family sought shelter in a cellar, only to be found by Russian soldiers the next morning. What followed was a scene of chaos and violence, with the invaders looting homes and violating the women without mercy.

Rosemann’s account is just one of many, highlighting the collective trauma of a community thrust into a nightmare. Her story echoes the countless screams that filled the nights, as women were dragged into hallways and raped, their cries mingling with the constant sounds of destruction.

The Brutality of the Red Army: A Tale of Unchecked Violence

Another eyewitness, Frau Frieda Schneider, recounts the terror that befell her and her neighbors in Breslau. Forced to hide in cellars, they endured ten days of fear and uncertainty. On February 18, 1945, amid these hellish conditions, a woman gave birth in a damp, dark cellar—a grim testament to life’s persistence even in the face of death. Yet, the horror did not spare the vulnerable. Schneider tells of a young mother who, despite holding her newborn child, was not spared from the brutality of the invading forces.

The atrocities committed by the Red Army were not isolated incidents of war; they were systematic acts of violence fueled by an environment where the usual moral constraints had been completely dismantled. Röhl’s detailed account, based on extensive testimonies, challenges the oversimplified narrative that these were merely acts of revenge. Instead, he argues that these crimes were perpetrated because they were allowed—because the usual prohibitions against such barbarity had been lifted in the chaos of war.

The Myth of Justified Retribution

In his book, Röhl also critically examines the widespread post-war narrative that sought to justify these atrocities as acts of retribution for the crimes of the Nazis. This argument, he contends, is deeply flawed. The notion that the brutalization of women, including the elderly and children, was somehow a justifiable response to the horrors inflicted by the German military, fails to hold up under scrutiny. These acts of violence were not merely spontaneous outbursts of rage by soldiers who had witnessed the devastation of their homeland. Instead, they were part of a broader, more sinister pattern of behavior that transcended the battlefield and spilled over into a wholesale assault on humanity itself.

Röhl points out that the soldiers who committed these heinous acts were often not the battle-hardened troops who had suffered losses on the front lines. Rather, they were young recruits, some from the far-flung regions of the Soviet Union, who had no personal experiences of German atrocities. Their actions, Röhl argues, were driven not by a desire for revenge but by the simple fact that they could. The collapse of law and order in the final days of the war created a vacuum where the basest human instincts were allowed to reign unchecked.

The Aftermath: A Legacy of Suffering

The legacy of these atrocities is one of enduring pain and trauma. The survivors of Breslau and Silesia were left to rebuild their lives in the shadow of unimaginable horror. The psychological scars, coupled with the physical devastation, created a landscape of suffering that persisted long after the war had ended. Röhl’s work serves as a stark reminder that the victims of these crimes—women, children, the elderly—deserve to have their stories told, free from the distortions of political narratives that seek to justify or minimize their suffering.

As Rolf Dietrich’s fictional journey in the Maier Files intertwines with the real horrors of Breslau, it serves as a powerful reminder of the personal tragedies that are often overshadowed by the grand narratives of history. The story of Breslau is not just a footnote in the annals of World War II; it is a testament to the resilience of the human spirit in the face of unimaginable cruelty.

Grim Statistics: The Toll of War in Breslau and Silesia

The fall of Breslau and the surrounding region of Silesia was not just a military defeat for Nazi Germany; it was a human catastrophe of staggering proportions. The numbers tell a gruesome story:

- Civilian Casualties: Of the approximately 1.2 million civilians who lived in Breslau before the war, it is estimated that around 60,000 to 80,000 perished during the siege and subsequent Soviet occupation. Many of these deaths were the result of starvation, disease, and the horrific violence inflicted by the occupying forces.

- Mass Rapes: It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of women in East Prussia, Silesia, and Pomerania were raped by Soviet soldiers. In Breslau alone, thousands of women were subjected to repeated assaults, with many taking their own lives to escape the torment.

- Displacement and Death: The mass exodus of civilians from East Prussia and Silesia, often referred to as the “Flight and Expulsion,” led to the deaths of an estimated 600,000 to 700,000 people. Many died from exposure, hunger, or were killed by advancing Soviet forces. The region’s pre-war population of nearly 5 million was decimated by war, flight, and forced expulsions.

- Overall Casualties in Silesia: Out of the 4.8 million inhabitants of Silesia (including those who had fled to the region from bombed-out areas), approximately 874,000 died due to war-related causes and subsequent expulsions. These figures include not only those killed in combat but also the elderly, women, and children who perished during the chaotic evacuation or were murdered by Soviet soldiers.

Remembering the Forgotten

The horrors of Breslau and Silesia during the final months of World War II and even after Germany’s surrender, remain a somber reminder of the depths of human cruelty. Klaus Rainer Röhl’s “Verbotene Trauer” sheds light on these dark events, challenging us to confront the uncomfortable truths of our past. In remembering these stories, we honor the victims and ensure that their suffering is not forgotten, buried beneath the justifications of history.

In the context of the Maier Files series, these historical events provide a haunting backdrop to the personal struggles of the characters, reminding us that history is not just a series of dates and events, but a tapestry woven from the lives of countless individuals, each with their own story of pain, loss, and resilience.