The hidden Pagan history of Europe, the persistence of its native religion in various forms from ancient times right up to the present day. Most people today are more familiar with native traditions from outside Europe than with their own spiritual heritage.

The Native American tradition, the tribal religions of Africa, the sophistication of Hindu belief and practice and the more recently revived Japanese tradition, Shinto, are widely acknowledged as the authentic native animistic traditions of their respective areas.

In marked contrast, the European native tradition, from the massive civilisations of Greece and Rome to the barely documented tribal systems of the Picts, the Finns and others on the northern margins of the continent, has been seen as having been obliterated totally. This tradition is presented as having been superseded first by Christianity and Islam and, more recently, by post-Christian humanism.

Pagan

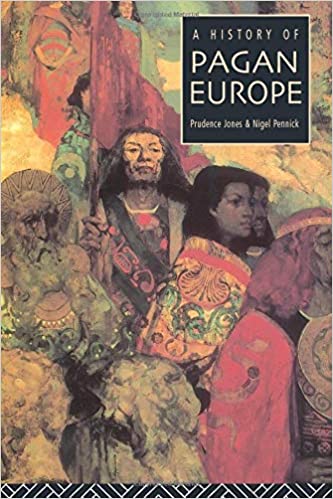

In this book (A History of Pagan Europe), the authors argue that, on the contrary, it has continued to exist and even to flourish more or less openly up to the present day, when it is undergoing a new restoration. The word ‘pagan’ (small ‘p’) is often used pejoratively to mean simply ‘uncivilised’, or even ‘un-Christian’ (the two generally being assumed to be identical), in the same way that ‘heathen’ is used. Its literal meaning is ‘rural’, ‘from the countryside (pagus)’ .

As a religious designation it was used first by early Christians in the Roman Empire to describe followers of the other (non-Jewish) religions, not, as was once thought, because it was mainly country bumpkins rather than sophisticated urban freethinkers who followed the Old Ways, but because Roman soldiers of the time used the word paganus, contemptuously, for civilians or non-combatants.

The early Christians, thinking of themselves as ‘soldiers of Christ’, looked down on those who did not follow their religion as mere stay-at-homes, pagani. This usage does not seem to have lasted long outside the Christian community. By the fourth century, ‘Pagan’ had returned closer to its root meaning and was being used non-polemically to describe anyone who worshipped the spirit of a given locality or paps.’ The name stuck long after its origin had been forgotten, and developed a new overlay of usage, referring to the great Classical civilisations of Greece and Rome, Persia, Carthage, etc.

European Renaissance

Early Christian writers composed diatribes against the Pagans’, by which they meant philosophers and theologians such as Plato, Porphyry, Plutarch, Celsus and other predecessors or contemporaries. Much later, when Classical literature resurfaced in the European Renaissance, the literati of the time composed essays on Pagan philosophy, and by the nineteenth century the use of the word as a near-synonym for Classical’ had become established.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, D.H. Lawrence’s literary group ‘The Pagans’ drew its inspiration from Greece and what he later called its ‘big, old Pagan vision, before the idea and the concept of personality made everything so small and tight as it is now’.

Lawrence’s terminology has overtones of more recent contemporary usage, where ‘Pagan’ is employed once more in its root meaning to describe a Nature-venerating religion which endeavours to set human life in harmony with the great cycles embodied in the rhythms of the seasons.

Pagan religions, in this sense, have the following characteristics in common:

— They are polytheistic, recognising a plurality of divine beings, which may or may not be avatars or other aspects of an underlying unity/duality/ trinity etc.

— They view Nature as a theophany, a manifestation of divinity, not as a `fallen’ creation of the latter.

— They recognise the female divine principle, called the Goddess (with a capital ‘G’, to distinguish her from the many particular goddesses), as well as, or instead of, the male divine principle, the God.

The Goddess

A religion such as Hinduism is Pagan, but Judaism, Islam and Christianity are obviously not, since they all deny the Goddess as well as one or both of the other characteristics. Buddhism, which grew out of the native Hindu tradition, is a highly abstract belief system, dealing with that which is beyond time and manifestation rather than with the interventions of deities in the world.

In its pure form it retains little in common with its Pagan parent. All three characteristics listed above are, however, shared by modern Paganism in its various forms with the ancient religions of the peoples of Europe, as this “The history of Pagan Europe” will show. In recent years many people of European origin have been drawing on the ancient indigenous tradition as the basis of a new religion for the twenty-first century.

This new religion, called neo-Paganism or simply Paganism, is most broadly a form of Nature-mysticism. It is a belief which views the Earth and all material things as a theophany, an outpouring of the divine presence, which itself is usually personified in the figure of the Great Goddess and her consort, the God or masculine principle of Nature. Between them, these two principles are thought to encompass all existence and all development. In some ways this is a new religion for the New Age.

Modern Paganism

Modern thought is represented in these two basic divinities whose influence is complementary rather than hierarchical or antagonistic. Present-day Pagans tend to see all gods and goddesses as being personifications of these two, in contrast to the situation in antiquity, when the many gods and goddesses of the time were usually thought of as truly independent entities. In its most widely publicised form, neo-Paganism is a theology of polarity, rather than the polytheism of ancient European culture.

But modern Paganism is also an outgrowth from the old European tradition. It has reclaimed the latter’s sacred sites, festivals and deities from obscurity and reinterpreted them in a form which is intended to be a living continuation of their original function. Followers of specific paths within it such as Druidry, Wicca and Asatru aim to live a contemporary form of those older religions which are described or hinted at in ancient writings, as in Iceland, where Asatru is a legally established religion, drawing its guidelines directly from the Old Norse sagas and shaping their outlook into a form which is continuous with the past but appropriate for the twentieth century.

At the opposite extreme, many neo-Pagans, in Anglo-Saxon countries in particular, follow no structured path but adhere to a generally Nature-venerating, polytheistic, Goddess-centred outlook which is of a piece with the general religious attitude chronicled here. Why has Paganism arisen again in modern Europe and America?

The great mother

The underlying impetus seems to have been first, the search for a religion which venerated the Goddess and so gave women as well as men the dignity of beings who bear the ‘lineaments of divinity’. This has been thought necessary by women whose political emancipation has not been paralleled by an equivalent development in their religious status. (Even in Pagan, polytheistic Hinduism the cult of Kali, the Great Mother, is one of the most rapidly growing popular religions at the present time.)

Secondly, in Europe and America a greater respect for the Earth has come into prominence. The ecological ‘green’ movement has gone hand in hand with a willingness to pay attention to the intrinsic pattern of the physical world, its rhythm and its ‘spirit of place’. This has led to a renewed recognition of the value of understanding traditional skills and beliefs and their underlying philosophy, which is generally Pagan.

And finally, the influence of Pagan philosophies from the Orient has gone hand in hand with this development, providing a sophisticated rationale for practices which might in former times have been dismissed as superstitious and unfounded. The Pagan resurgence thus seems to be part of a general process of putting humanity, long seen by both the monotheistic religions and by secular materialism in abstraction from its surroundings, back into a more general context.

This context is both physical, by reference to the material world understood as an essential part of life, and chronolog-ical, as shown in the search for modern continuity with ancient philosophies. The ancient religions are often not well known outside their areas of academic specialisation, and the evidence for their continuation is often misunderstood or misrepresented as ‘accident’ or ‘superstition’.

Pagan history

https://amzn.to/2Y4cf2D

It is the evidence for such continuity which this book “History of Pagan Europe” investigates. The area of the study covers the whole of Europe, beginning with Greece and the eastern Mediterranean, home of the earliest written records; continuing west by way of Rome and its Empire; then through the so-called ‘Celtic fringe’ of France, Britain and parts of the Low Countries; then to what are now Germany and Scandinavia; and finally to eastern and central Europe, the Baltic states and Russia, which (apart from Russia and the South Slav states) emerged most recently into historical record.

Europe in this sense is a geographical entity divided roughly into north and south by the Alps, and into east and west by the Prague meridian. After the Holy Roman Empire in the west and the Byzantine Empire in the east defined Christendom between them, Europe became a cultural unity, and its native religious tradition disappeared area by area into relative obscurity. This vital, yet half-hidden, European tradition is what we put on record here.

The centuries covered run from the dawn of recorded history to the present day: different timescales in different areas. The process of interpreting Stone-age remains is too extensive and currently too embattled to be capable of fair handling in the context of this book.

It is enough to describe what people believed and what they did, at what times and in what places. In this lies a fascinating story, and we shall begin with the earliest records.

src. Prudence Jones & Nigel Pennick “A History of Pagan Europe”