In the last days of paganism in Germany, the druids’ sacrifices were subject to punishment by death at the hands of the literalist Christians. Nevertheless, at the beginning of springtime the “druids” and the populace sought to regain the peaks of the mountains so that they could make their sacrifices or experience their celebrations at these remote locations, intimidating and chasing off the Christians (usually through the latter’s fear of the devil). The legend of the first Walpurgis Night is supposed to be based on such attempts.

At its center is the Walpurgis Night, a supposed celebration of evil that is named after a British saint whose good deeds took place deep inside what is now Germany. That fabled convergence of good and evil was treated in literature in a short ballad and two topically related scenes of the Faust tragedy by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), a pantheistic scientist, draftsman, and poet. Many of the legends of the Walpurgis Night center on the Brocken, the highest peak of the Harz Mountains.

As you are a reader of Maier files you already know that this region also plays a significant role in the series.

The last days of paganism

Throughout Western European spheres of influence the night of April 30 is home to a conspicuously secular celebration. It is known in Germany as die Walpurgisnacht (Walpurgis Night), alternatively in the United Kingdom and the United States as Beltane or May Eve; in Italy as la notte di Valpurga, Beltane, or Calendimaggio; in Spain as la noche de Walpurgis, and in France as La nuit de Walpurgis or simply La Walpurgis. After Christmas and Easter it is one of the major holidays in Finland and Sweden (VapunAatto and Valborgsmässoafton, respectively). Its origins antedate written records, and it is host to a wide variety of popular and commercial revelries.

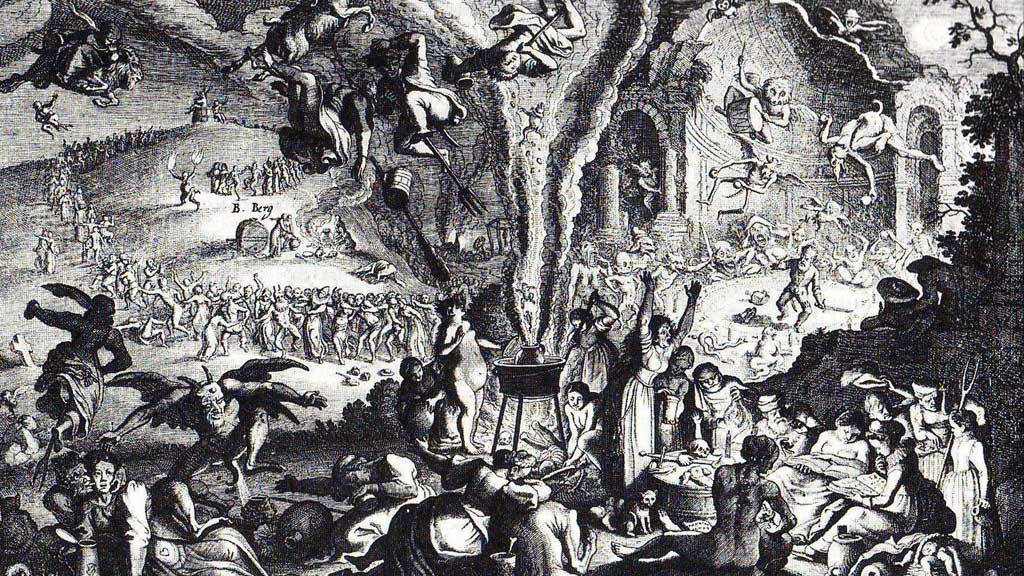

Like its autumn counterpart, Samhain or All Saints – Halloween, it is practiced today primarily in folk culture. Also like Halloween, the Walpurgis Night celebrates magic and the supernatural, the profane alternative to the predominantly monotheistic cultures of mainstream society. And it, too, is home to countless ghost stories and a wide variety of folk tales populated by witches, werewolves, and other supernatural beings. Unlike Halloween or Samhain, however, the Walpurgis Night is equally at home in cultivated and ordinary areas of endeavor. It has been the subject of paintings and other visual artworks by Albrecht Dürer, Hans Baldung Grien, Eugène Delacroix, and Paul Klee, and of ballets by George Balanchine, Evald Smirnov, and Leonid Lavrovsky, among others.

The Walpurgis Night shares with many longstanding cultural practices the general theme of a fundamental conflict between Old and New. As its long history and conspicuously secular character suggest, the Old is essentially Europe’s preChristian religions; the new, European Christianity as a whole. The split also entails extensions (or subsets) of each of these, however. The political history by which Christianity assumed predominance as the religion of mainstream society in Western Europe aligns it with the late Frankish, Merovingian, and early Carolingian kingdoms (ca. 500–800 CE). The resultant political and religious structure, adjoining with the New generally, may be termed Western Christendom, distinguishing it from Byzantium to the East and Anglo-Saxon Christendom in the British Isles.

Women’s wisdom

The family structures of the Eastern Germanic tribes were oriented not around the concept of the independent individual, but around the sib (sippia, sippa), the community of free individuals, both living and dead, who were related through either blood or marriage. Despite significant differences in worship customs and eschatology (a part of theology concerned with the end time), until fairly late in their history the Germanic tribes conducted most of their worship services in the open air rather than in temples, with a special preference for hilltops, mountaintops, and other elevated sites. They shared a deep reverence for the forest and a belief in women’s—especially older women’s—wisdom, particularly their powers for divination.

The surviving evidence suggests that the Walpurgisnacht acquired its name through the convergence of several figures and dates that are at turns loosely related or unrelated: a pagan goddess (or several pagan goddesses) whose history antedates the documented Walpurgis Night legends. There is some possibility that the term’s use derives from a prehistoric Germanic cult of a goddess named Walburg. The Walpurgiskirche formerly situated in Gröningen (near Magdeburg) was supposedly named after this goddess, and far more west the Walburgakerk in Veurne in Flanders, was supposedly built on the site where sacrifices to her had been made.

That region Veurne – Ypres also have a profound very old witch lore. Equally possible is that the term is applied in derivation from two Old High German and Norse elements that occur in Saxon and Norse mythology in connection with Wuotan: the Old High German prefix wal- and its Norse counterpart val- (to choose, select, pick out), and burg / borg (castle, stronghold). According to myth, Wuotan and the goddess Freia celebrated the beginning of springtime with a group of snow-white, winged virgins in a special section of Walhalla named the Walburg. But these graceful young females achieved that state of beauty through a process of transformation—for the blissful month of carnal celebrations was preceded by the stormy months of competition for the godly consort.

Abbess Walpurgis

More easily documented are the life and works of the eighth-century Benedictine abbess Walpurgis. Although Walpurgis’s biography is suffused with fictitious anecdotes, one of the remarkable events of her life may relate to the instrumental introduction that precedes Mendelssohn’s setting of Goethe’s cantata in Goethe’s 1799 ballad “Die erste Walpurgisnacht,” and one further event offers a parallel to the poem’s theme of darkness and light. She brings the light.

The Brocken and the Harz are located between the Weser and Elbe rivers northeast of Göttingen and southwest of Berlin, east of most of the Frankish – Saxon conflicts and northwest of St. Walpurgis’s domains in Heidenheim and Eichstätt. This location may be partially responsible for their reputation as places of eerie and unexplained happenings, for the Brocken was remote from all the advancing fronts of Christendom during the Carolingian era and home to the fierce Saxon tribes whose ritual sacrifices and other pagan practices, in the eyes of their Christian adversaries, immediately proclaimed their alliance with the devil.

Brocken mountain

The dense forests, steep, craggy slopes, and narrow valleys of the range constituted some of the most challenging terrain faced by the advancing Christian front. The summit of the Brocken itself was deemed unattainable to all humans except experienced hikers for centuries more. Those who reached it found a sparsely vegetated peak shrouded with mists and populated with various bizarre rock formations, among them the imposing and grotesque formations that eventually became known as the Teufelskanzel (devil’s chancel) and Hexenaltar (witches’ altar).

But if the difficult terrain of the Harz, its history as one of the last strongholds of heathenism, and its uncanny apparitions pointed to the Brocken as home to Christendom’s enemies, this reputation was solidified by one other, far uglier cultural event: the fascination with witchcraft and sorcery that began in the fourteenth century and culminated in the notorious witch trials and murders of the fifteenth, sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries.

Have a nice Walpurgisnacht!