The Delphic idiom: gnothi seauton (“Know thyself”), assigned to Pythagoras, carries an extended history in the Western world. It grew to become popular all through of the teachings of Socrates as well as Plato, along with the query to obtain self-knowledge was, from that point on, much more a challenge of philosophy than of religion.

In the religions, Western man made larger attempts to attaining understanding of the characteristics and meaning of the world altogether and towards redemption from suffering than he actually did for empirical clues about his very own makeup. In the history of philosophy, however, we note that thinkers ever since Plato have focused much more on an understanding of conscious contemplating rather than on the elucidation of the individual as a whole.

Philosophy

It turned out in the history of philosophy that mainly the introverted thinkers who made an effort, as it were, to delve reflectively into the inner back-ground of their emotional and mental functions. All in an obsessive search for their origins. Saint Augustine, Descartes, and Kant are enlightening types of this distinctive line of thought. Everybody who dug deep enough into the back-ground of awareness achieved, in one manner or another, something strange and irrational which they typically stipulated with the term of “God.”

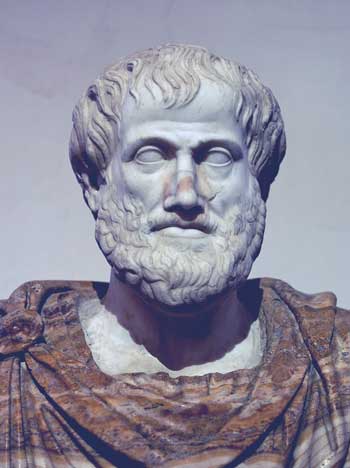

However, an unbiased psychology by means of impersonal experimental observation of the human mind started off with Aristotle and resulted in a variety of concepts concerning man’s so called pathē, emotions, affects, et cetera, along with regarding his social drives.

However, an unbiased psychology by means of impersonal experimental observation of the human mind started off with Aristotle and resulted in a variety of concepts concerning man’s so called pathē, emotions, affects, et cetera, along with regarding his social drives.

The result of this direction in the analysis of human characteristics can be found in present-day behaviorism in its numerous wide-ranging gradations. These types of efforts to account for human nature have revealed a lot that is certainly important.

Yet over and over again we are stunned that along the way it is particularly the source of self knowledge which has been quite little looked into, or even generally speaking not at all, and which nowadays we look upon as the most important treasury of information regarding our-selves: the unconscious, certainly in its manifestation in dreams.

C. G. Jung

To this day the dream has remained an unexplained life phenomenon, having its roots deep in the physiological life processes. It is a normal, universal manifestation in all of the higher animals. We all dream about four times a night, and if someone prevents our dreaming, serious psychic and somatic disturbances result. C. G. Jung provisionally identified as relatively certain facts the following aspects of the dream:

The dream has two roots, one in conscious contents, impressions of the previous day, and so forth, the second in constellated contents of the unconscious. The latter consists of two categories:

- constellations which have their source in conscious contents;

- constellations arising from creative processes in the unconscious.

The meaning of a dream can be formulated as follows:

- A dream represents an unconscious reaction to a conscious situation.

- A description of a situation which has come about as the result of some conflict between consciousness and the unconscious.

- A representation of a tendency in the unconscious whose purpose is to effect a change in a conscious attitude.

- A depiction of unconscious processes which have no recognizable relation to consciousness.

Understanding

Understanding

One can understand every dream as a drama in which we ourselves are everything. That is, the author, director, actors, and prompter, as well as the spectators. If one tries to understand a dream in this way, the result is a startling realization for the dreamer of what is happening in him psychically, “behind his back,” so to speak. The moment of surprise lies in what Jung called the compensatory or complementary function of the dream. This means that the dream almost never represents something already conscious. It rather brings either contents which balance a one-sided attitude of consciousness (compensatory) or completes what is lacking in those contents of consciousness. (complementary).

Who “Composes” a Series of Dream Images?

Who or what is this miraculous something that composes a series of dream images? It must be a being of the most superior intelligence—judging from the depth and cleverness of dreams. But is it a being at all? Does it have a personality or is it something more like an object, a light or the surface of a mirror? In Memories, Dreams, Reflections Jung calls this something “personality No. 2.” He experienced it first as a personal or at least a half-personified being.

Personality No. 2 is the collective unconscious, which Jung also later called the “objective psyche”. For it is experienced as not belonging to us. (In the historical past such phenomena were looked upon as “spirit powers.”) It is a “something” which is experienced by the subject ego as its opposite. Like an eye, so to speak, which observes one from the depths of the soul. In his Philosophia meditativa, Gerhard Dorn, a follower of Paracelsus, has given a most illuminating description in many respects of this experience.

Self-knowledge

In his view, the alchemical opus is based on an act of self-knowledge. This self-knowledge, however, is not what the ego thinks about itself, but something quite different. Dorn says, “But no man can truly know himself unless first he see and know by zealous meditation… What rather than who he is, on whom he depends, and whose he is, and to what end he was made and created, and by whom and through whom.”

With the emphasis on “what” (instead of “who”) Dorn stresses a non-subjective real partner which he seeks in his meditation and in his self-knowledge. And by this he means

nothing other than the image of God embedded within the soul of man. Whoever observes this and frees his mind from all worldly cares and distractions, “little by little and from day to day will perceive with his mental eyes and with the greatest joy some sparks of divine illumination.”

Whoever in this way recognizes God in himself will also recognize his brother. Jung called this inner center, which Dorn equates with the god-image, the Self. In Paracelsus’s view, man learns about this inner light through his dreams. “As the light of nature cannot speak, it buildeth shapes in sleep from the power of the word.”