Who’s Odin? To find Odin’s origins, how far back must we go? Although the most likely explanation for Snorri’s attempts to connect the Æsir with Troy is medieval literary fashion, it is tempting to see a possible source in folk memories of the migration of the Yamnaya culture from the steppes of the Caucasus and Urals into northern Europe four or five thousand years ago.

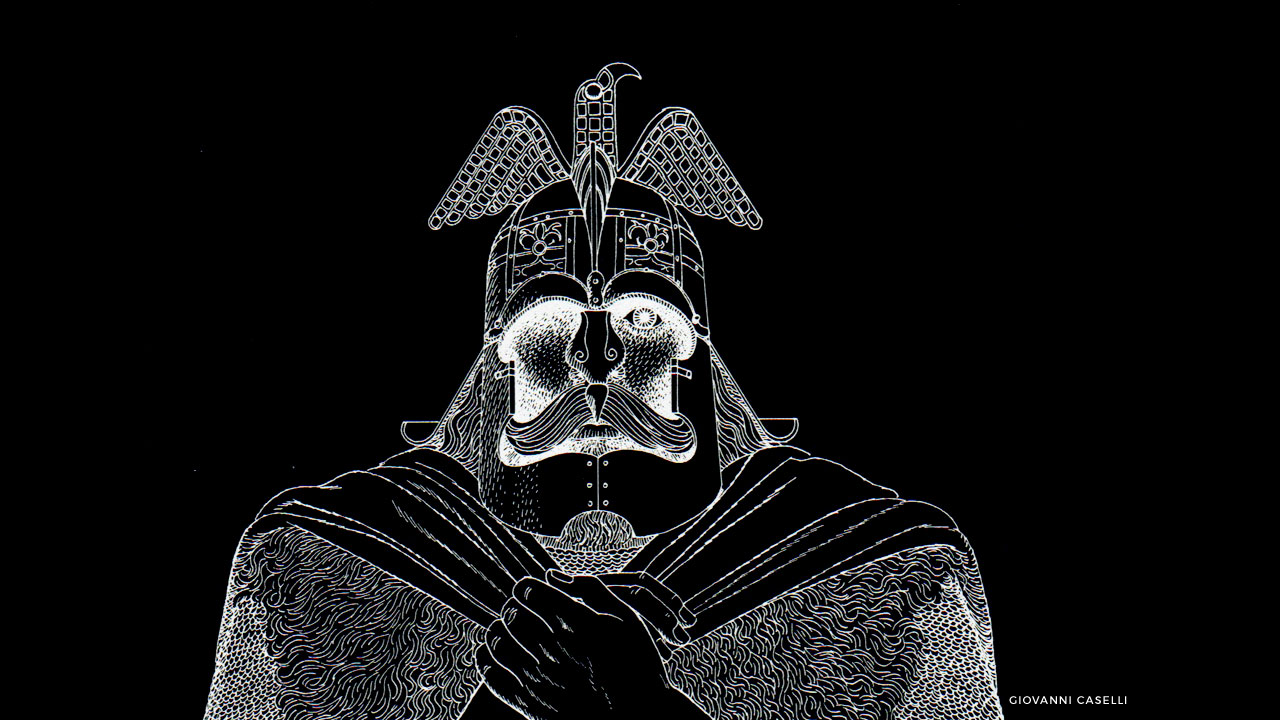

Shaman

Is Odin a shaman? Grundy and other critics of this theory point out that properly speaking, a “shaman” operates in a tribal cultural context quite different from the world of the Viking Age, much less our own. Certainly Odin’s other functions argue for a very different identity. However, if we look at Odin’s roles as a god of magic and battle, it is possible to see him at an earlier period as the shaman who migrated with the tribes, working magic to encourage their warriors and terrify their foes.

The Romans

Most of our written information on the origins of Scandinavian culture comes from sources such as the Eddas, The Lives of the Norse Kings (Heimskringla) by Snorri Sturlusson, and the history of the Danes by Saxo Grammaticus, all written down in the 12th to 13th centuries. These sources begin with events from the Migrations Period (4th through 7th centuries), when many different Germanic tribes were moving south and west into Europe. We also have a few references in chronicles and inscriptions from the Roman Empire. Even at that date, there is evidence for what H. M. Chadwick calls “the crafty, magical, bardic side (of Odin) on the one hand, and the warlike side on the other” (Chadwick 1899, 29).

Wodanaz

The Romans dealt with the abundance of deities they encountered as the Empire expanded by the interpretatio Romana—identifying the native gods as local forms of whatever Roman god they most resembled. Germans who served with the Roman army and the Romano-German population living along the border of Germania felt that the Roman equivalent of Wodanaz was the Roman Mercurius (who himself overlaps, but is not quite the same, as the Greek Hermes). Mercurius is associated with travel, commerce, and communication and was also a psychopomp who conducted the souls of the dead to the Otherworld.

In Cologne, the cathedral was built on the ruins of a Roman temple to Mercurius Augustus. The temple was erected to honor the Emperor Titus, but if I were trying to describe Odin’s role as a god of kings in Roman terms, this aspect of Mercurius is the name I would use. According to Tacitus, a Roman historian who collected information from officers who had served in Germania, the chief god of the Germans was “Mercurius” (Tacitus 1964, Germania 9), who was given human sacrifices.

Mercurius

The Greek Hermes and the Roman Mercurius are gods of communication, guides for the dead, magicians, and tricksters—categories that certainly apply to Odin. However, Hermes generally facilitates, rather than originating, action. The messages he carries are those of Zeus and other gods, not his own, whereas Odin speaks to the dead and sometimes is responsible for their deaths rather than serving as a guide.

Mercurius and Hermes come closer to Odin in his aspect as Hermes Trismegistus, who in the Hellenistic period was master of esoteric wisdom, though Hermetic magic tends to be far more ceremonial than the skills attributed to Odin in the Ynglingasaga. Finally, the tricks played by Odin have a deeper purpose, and often a deadlier result, than the relatively innocent pranks ascribed to Hermes.

Apollo

Diana Paxson’s explorations have led to speculate on links between Odin and the deities Apollo and Lugos. His Irish incarnation, Lugh Samildanach, is good at everything. In his Gaulish form, Lugos sent ravens to guide his people to found the city of Lugdunensis (Lyons). Diana Paxson is not the only one to have noted these similarities. In The Quest for Merlin, Nikolai Tolstoy proposes that Merlin may have been a priest of Lugh/Odin.

Before acquiring his associations with the sun, Apollo was a god of poetry and healing. A plate found at Delphi shows him accompanied by a crow. But Apollo also has a dark side in which he runs with the wolves and shoots plague arrows with his silver bow.

He and Odin are not the same god, but it looks like that they sometimes hang out in the same bar. Another deity who is sometimes linked with Odin is the Irish battle and crow-goddess, the Morrigan. According to author Morgan Daimler, who has worked with the Morrigan for many years, they have a lot in common.

Morrigan

Although it’s fairly popular to equate the Morrigan to the Valkyries, Paxson finds that a bit of an unequal comparison and says that it makes more sense to compare her to the Valfather than to those who are known to serve him.

The two deities have a variety of things in common including a tendency in mythology to interfere directly in human affairs and a reputation in modern paganism to be active among their followers.

Both the Morrigan and Odin are known to sway the outcome of battles in favor of those they want to win and are associated with the dead. Both are also associated with prophecy and strategy, and both are known for appearing in disguise or presenting themselves to people in stories as someone else.

And of course Odin and the Morrigan are both strongly associated with magic of various kinds. They are not, however, identical, as the Morrigan is not known to wander as Odin does nor is she striving to gain wisdom or to prevent any battles, such as Ragnarok.

Wodan

By the time the migrating Germanic tribes encountered the Romans, Wodan was well established. In his Annales (13:57), Tacitus, writing in the first century, tells of a war fought between the Hermunduri and the Chatti for possession of a sacred salt river. The victorious Hermunduri then sacrificed the entire beaten side, with all their arms and possessions, to “Mars and Mercury’ that is, Tiwaz and Wodanaz. This suggests that Odin and Tyr played complementary roles in warfare. The origin story of the Lombards, recounted by Jordanes in the 6th century, portrays Godan (Wodan) in a more kingly role, tricked by his wife into giving the tribe both victory and a name.

Viking age

The God of Skjalds and Kings Whatever his origins, by the Viking Age, Odin appears as the leader of the Æsir, patron of poets and kings. Until the conversion to Christianity was complete and the task of reporting history taken over by monkish chroniclers, it was the poets who recorded the deeds of the kings and heroes.

The livelihood of the skjalds and the fame of the king were equally dependent on that relationship. We should not be surprised by the number of battle names recorded for Odin—the kings made offerings to him for victory, but there are only so many ways to describe a battle—the poets were probably asking the god for more words. In the Younger Edda, Snorri Sturlusson introduces Odin as All-father. Nonetheless, a few paragraphs later, we are given a list of additional names for the god, indicating that, despite the propaganda, his other aspects were still known. Bynames such as Vidrir (“Weather god”) and Thund (“Thunder”) link him to the wind and storms; names such as Hagvirk (“Skillful Worker”) and Thrór (“Thrive”) give him an even broader sphere.

Even though Odin received sacrifice mostly from Norse nobility and kings, he is not a sovereign in the medieval sense of the word. Indeed, our image of Odin as “king of the Norse gods” seems to owe more to later writers brought up on classical mythology than it does to the Eddas.

Src. Odin: Ecstasy, Runes, & Norse Magic by Diana Paxson

Delve deeper with this excellent book! https://amzn.to/3cteUsN