Women today tend to trivialize goddess Frigg’s functions. If you try to unravel the different levels, connections, storylines and hidden meanings in Maier files, getting into the world of Disir and ancient European goddesses can be very helpful. An interesting read is the original work of Mrs. Karlsdóttir.

Mrs. Karlsdóttir in her book Norse Goddess Magic states that women today tend to trivialize goddess Frigg’s functions. The main reason is that some women who are still trying to disentangle themselves from unfair societal restrictions, many of which stem from the medieval Christian social structure with its roots in Roman feudalism, a goddess devoted to marriage, children, relationships, and domestic skills is much less appealing. But, she says, we need to try to appreciate what these skills meant in the context of the society in which the figure of Frigg originated.

Providing fire, food, drink, clothing, and bedding, as well as things like soap and candles, for all the inhabitants of a Teutonic or Norse farm was much more complex than microwaving a few leftovers. If the housewife didn’t plan carefully through the winter and spring, the consequences of running out of something around, say, February, were very serious. Surviving in a cold and harsh environment depended on it!

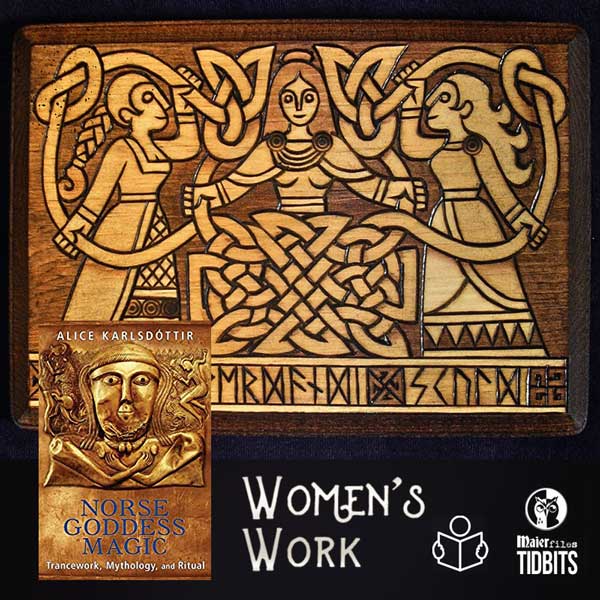

Women’s Work

The brewing of ale and mead was generally considered the province of the women, and in Norse and Teutonic society this was more significant than merely hosting a few drunken brawls. Ale was viewed as a spiritual substance. It was imbued with the power to unite both gods and humans. Without ale the high feasts and rituals were impossible.

The brewing of ale and mead was generally considered the province of the women, and in Norse and Teutonic society this was more significant than merely hosting a few drunken brawls. Ale was viewed as a spiritual substance. It was imbued with the power to unite both gods and humans. Without ale the high feasts and rituals were impossible.

The forebears used mead and ale in worship and in the practice of medicine and magic. But more important they utilized it to formalize councils:

- sealing important agreements and bargains, such as treaties, marriages, and the transfer of property;

- celebrating festivals;

- displaying hospitality and goodwill; and

- honoring all important life occasions.

The validation of contractual agreements depended on good beers and alcoholic beverages. The better the beers the more binding the contract.

The sharing of drink was also a key element in religious ritual.

Brewing

The processes of both brewing and baking have something of the holy and mysterious about them, even today. One takes these seemingly inert ingredients—grain and milk, honey and water—and adds this magical substance known as yeast (in reality the living cells of a small fungus), and after a period of hours or months, the original ingredients have mysteriously changed, transformed into something else—the bread rises, the ale or mead ferments.

In earlier times, when fermenting was left to the mercy of wild yeast from the air, this change must have seemed even more miraculous. Therefore, brewing was probably endowed with the formality of ritual, incorporating special ceremonies and practices. People prepared their ale with great care. They feared that any carelessness might keep the brew from becoming strong enough .This would be not just an inconvenience but a sign of ill luck and misfortune.

Woman’s skill

Thus a woman’s skill in brewing was more than just proof of her housewifely prowess; it was proof of her holiness, her luck, and her kinship with the gods. Hálfs saga gives an example of the significance of brewing. King Alrek had two wives, Geirhild and Signy. Only one of them could become queen. So they had an ale-brewing contest to determine which of them would wear the title.

Spinning and weaving, like brewing, have a magical side to them. The act of drop-spinning involves taking a bunch of loose fibers on a distaff in one hand and forming a thread by a combination of twisting and drawing out fibers in a continuous line with the other hand. The twisting process is aided by the turning of the spindle, around which the finished yarn is wound to prevent the thread from unraveling.

Germanic worldview

The spinning process is suggestive of the power that brings things into manifestation. The shaping might that defines the fate of all that exists. For this reason, spinning was associated with the Norns, the Norse incarnations of time and causality. Paul C. Bauschatz, (author of The Well and the Tree) associates the name of one of them, Verdandi (“Becoming”) with various root words that all relate to the concept of “turning.” The spiral-like movement of spun thread reminds one of the cyclical nature of the Germanic worldview, in which life was seen as a continuously repeating pattern rather than a linear progression.

Weaving is also associated with the Norns and with magic. It is the process of forming a textile by interlocking two sets of threads, the passive, lengthwise warp with the active, crosswise weft, or woof. This process is dependent on the interconnectedness of the threads and hence is often seen as symbolic of the web of life, where lives and events overlap to create a pattern that is only observable by stepping back to view the finished product as a whole.

Goddess of handicrafts

The goddess Holda gave linseed as a gift to the humans. Linen is the cloth made from the fibers of the flax plant. It is for sure one of the most difficult and challenging fabrics to spin and weave. Thus is an appropriate symbol for the goddess of handicrafts. The practice of harvesting and preparing flax and linen is to this day a ritualized process, fraught with tradition and secrecy.

The women for instance first removed the tough and woody flax stalks. Then they laid the flax out in the fields for about six weeks to absorb the dew. After a second drying, the fibers, which look remarkably like human hair, are cleaned and combed. They are difficult to work with because of their lack of elasticity. The best results are obtained from “wet-spinning” and weaving in rooms heavy with humidity. In fact, Europeans used to weave linen in caves, one of Holda’s favorite dwelling places. Techniques for finishing the linen vary and are usually carefully kept secrets!